The Death of Messiah: Human Agency and Divine Necessity

In the first days of 2020, the website of the influential evangelical magazine Christianity Today ran a bold critique of antisemitism entitled, “Killing Jesus’ Brothers and Sisters.” The op-ed was a clear and forthright—and welcome—condemnation of historical antisemitism as it has been conveyed through centuries of Christian doctrine and rhetoric. The op-ed’s positive impact, however, was marred by a troubling phrase, highlighted below:

It is uncomfortable to say today that Jesus was killed by the Jews. And for good reason: That has led to the most vile and ugly racism the world has ever known. Theologically, it is crucial to say that we killed Jesus. All of us, Jew and Gentile. But for the sake of this article, let’s take note of this as well: Jesus was killed by his people the Jews.1

The paragraph acknowledges that, “we killed Jesus. All of us, Jew and Gentile,” but the final phrase remains troubling. Apparently this phrase raised enough concern that it was quickly amended to the version that appears currently: “Jesus was killed at the instigation of the Jews, who chanted, ‘Crucify him! Crucify him!’ forcing the hand of a weak-willed Pilate.”2 This modification is an improvement over the original, but the phrase “the Jews” still suggests a unique Jewish responsibility for the death of Jesus, a blame borne by individual Jews simply because they are Jewish.

Historian Deborah Lipstadt speaks of the “charges” of corporate Jewish guilt and explains their origin:

The historical template for these charges is to be found in the New Testament’s depiction of the death of Jesus. Irrespective of the fact that everyone involved in the story was Jewish—except for the Romans who did the actual crucifixion—the way the story has been told by generations of Church leaders is that “the Jews” killed Jesus.3

“Killing Jesus’ Brothers and Sisters” concludes with a bracing call to repentance, which author Mark Galli rightly notes “is not a one-time event but a lifelong journey.”4 Given the deep roots of Christian antisemitism, repentance may be not only a lifelong journey but a multi-generational one. It includes a responsibility to address the way the story of Yeshua has been told and promote a more accurate—and more redemptive—reading.

The notion that Luke portrays “the Jews . . . forcing the hand of a weak-willed Pilate” persists today, with the implication that Luke himself holds the Jewish authorities more responsible than the Romans.5 In the Book of Acts, however, Luke provides for a new “template,” to use Lipstadt’s terminology, for interpreting the trial and death of Yeshua, and for answering the question, “Who was, and is, responsible?” Luke is an appropriate source for this template because of his interest in history.6 It may not be accurate to describe Luke as a historian in the modern sense, but he writes with an interest in the historical characters and dynamics at work in the events that he portrays.

In contrast with most modern historians, however, Luke’s perspective is also theological. “In fact the focus of both Luke and Acts is primarily theocentric. . . . We are talking about the mighty deeds of God performed on the stage of history by and through Jesus and his followers.”7 This historical-theological perspective provides a template far more nuanced and profound than the accusations and innuendos of Jewish corporate guilt. This paper examines three key passages in Acts that help frame this template and concludes with a scene from the final chapter of Luke’s Gospel to consider human agency and divine necessity in the death of Messiah.

1. Peter’s Sermon on Shavuot

Peter concludes his explanatory sermon on Shavuot, the day of Pentecost, with a poignant warning to his Jewish audience about their response to “this man,” Yeshua of Nazareth:

This man, handed over to you according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of those outside the law. . . . Therefore let the entire house of Israel know with certainty that God has made him both Lord and Messiah, this Jesus whom you crucified. (Acts 2:23, 36)8

This rhetoric sounds like an ascription of Jewish corporate guilt: the “entire house of Israel” should “know with certainty” that one crucified in their holy city has been made both Lord and Messiah. But much depends on properly understanding the “you” whom Peter is addressing in verse 23, which is not synonymous with “the entire house of Israel” in verse 36. Peter’s message is for all the house of Israel, but he is speaking it directly to “you,” the crowd before him, which includes individual Jews who were actually involved in turning Yeshua over to Rome, “those outside the law,” for execution. “Some of those responsible are in Peter’s current audience, so Peter speaks of ‘This Jesus . . . you crucified.’ ”9 He wants the entire house of Israel to know that this one is Messiah—the same one that you particular Jews handed over to Rome. The NRSV properly treats “this Jesus whom you crucified” as a parenthetical phrase, defining the “him” of the preceding phrase.

Peter’s reference to the entire house of Israel in his conclusion echoes the mention of “devout Jews from every nation under heaven” in the prelude to his sermon. The worldwide Jewish community is represented here in Jerusalem, where these Jewish worshipers have gathered for the festival of Shavuot (Exod 23:17; Deut 16:16). Furthermore, these Jews are described as “devout” (eulabes, 2:5), the same Greek word Luke uses to describe Simeon, who was “righteous and devout, looking forward to the consolation of Israel” (Luke 2:25), and the “devout men” who carry Stephen to his burial (Acts 8:2). The devout quality of the Jews in Acts 2 is revealed by their making the pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the festival, in accord with the Torah, just as Yeshua’s devout parents make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem with him for Passover at the beginning of Luke (2:42ff). The devout Jews from every nation, then, are legitimate representatives of the entire house of Israel.

Peter’s point is not to blame this diverse Jewish crowd of worshipers, but to call them to repent, be forgiven, and receive the gift of the Spirit, present among them as evidence of Yeshua’s resurrection and enthronement at God’s right hand (2:32–38). This call to repentance is not triggered specifically by their rejection of Yeshua, in which only some of the crowd directly participated, but by their more general need to return to God and his ways—a return required even of devout individuals who seek to align with God’s standards.

Later in Acts this same combination of “repent, be forgiven, and receive the Spirit” will be offered to gentile audiences as well as to Jewish audiences. Indeed, the surprise in Acts isn’t that Jews, who are supposedly uniquely guilty, can repent, but that gentiles can repent too (Acts 11:18; cf. 17:30).

In sum, it appears that Luke, like Paul, believes that the gospel and its salvation is for the Jew first, but also for the Gentile (cf. Rom. 1:16). This of course implies that both Jews and Gentiles need to repent, believe, and be saved through faith in Jesus.10

In Acts 2, however, the repentance of gentiles is not in view. Instead Peter briefly introduces a theme that will be developed more fully in our next passage: the death of Messiah entails, or indeed requires, collusion between Jews and gentiles. Those Jews in Peter’s audience who crucified and killed Messiah did so—could only do so—“by the hands of those outside the law,” that is, gentiles who held the governing authority. This is a fuller answer to the question of human responsibility for the death of Messiah than simply ascribing it to “the Jews.” Peter also notes that the betrayal and death of Messiah happened “according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God.” Of course, this mysterious divine oversight of the matter doesn’t eliminate human responsibility, but it alerts us that something greater is at play.

2. The Community Prayer

Sometime after Shavuot, the temple authorities arrest Peter and John for “proclaiming that in Yeshua there is the resurrection of the dead” (Acts 4:2).11 The next day the authorities release Peter and John with a stern warning. The apostles return to their friends to report what had happened.

When [their friends] heard it, they raised their voices together to God and said, “Sovereign Lord, who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and everything in them, who through the mouth of our father David, your servant, said by the Holy Spirit,

‘Why did the Gentiles rage,

and the peoples imagine vain things?

The kings of the earth took their stand,

and the rulers have gathered together

against the Lord and against his Messiah.’

For in this city, in fact, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, with the Gentiles and the peoples of Israel, gathered together against your holy servant Jesus, whom you anointed, to do whatever your hand and your plan had predestined to take place.” (Acts 4:26–28)

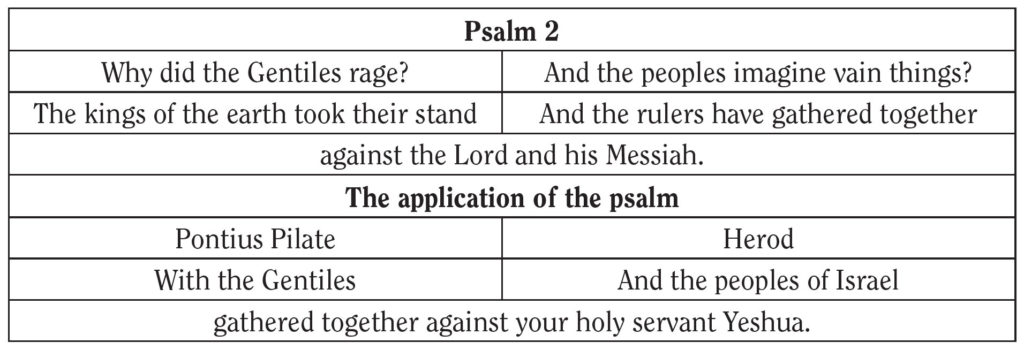

This prayer employs the words of Psalm 2 to illuminate the whole drama of Yeshua’s arrest and execution that had just taken place. By laying out the words of the prayer in a table we can see the logic of its treatment of Psalm 2.

The messianic assembly casts Pontius Pilate and the gentiles of his time in the role of “the kings of the earth” and “the Gentiles” in the psalm. “Herod” and “the peoples of Israel” in his time parallel “the rulers” and “the peoples” in Psalm 2. The climax in both versions comes as Jews and gentiles gather together “against the Lord and against his Messiah”—identified here as “your holy servant Yeshua.” As in the psalm itself, so in the prayer in Acts, “To be noted particularly here is reference to the close relationship between [the Lord] and his anointed one. To resist the One is to resist the other.”12

The venerable Christian commentator F. F. Bruce provides a slightly different summary of this prayer, which also recognizes the Jewish-gentile collusion that the prayer envisions:

The Gentiles raged against Jesus in the person of the Romans who sentenced Him to the cross and executed the sentence; the “people” who imagined vain things were His Jewish adversaries; the kings who set themselves in array [“took their stand,” NRSV] were represented by Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee and Peraea (cf. Luke 23:7 ff.), while the rulers were represented by Pontius Pilate.13

Despite varying details of interpretation, it’s clear that Acts 4 employs Psalm 2 to portray the Jewish-Roman collusion that Peter had referred to in passing in Acts 2. This collusion involves the governing authorities of the two great components of humankind. The psalm itself, of course, doesn’t refer to Rome or Romans, but to the “Gentiles” and “the kings of the earth.” In other words the psalmist looks beyond his specific historical setting to a remarkable convergence of Jews and gentiles—the two distinct, and often opposed, components of humankind—who have joined forces to oppose the Lord and his Messiah. “The hyperbolic sweep of biblical poetic idiom already transposes what might well have been a local political uprising into something like a grand global confrontation.”14 In the same spirit, Luke’s portrayal of Jewish-Roman collusion in the first century directs the psalmist’s prophetic indictment of rebellion not so much against Rome or Jerusalem as against humankind in general.

So who’s responsible for the death of Messiah? The Jewish and Roman perpetrators in the crucifixion represent Israel and the nations, all of humankind. The execution of Messiah in first-century Jerusalem was the culmination of human sinfulness going all the way back to Adam and Eve. The Jews and gentiles in charge, representing all of humankind, resisted God and his anointed one because it was in their nature to do so. Ascribing a unique corporate guilt to the Jewish people sidesteps the case being built in Acts against humanity as a whole, and ignores the overriding purpose of God that drives all the events surrounding Messiah’s death.

3. Paul’s First Apostolic Message

The absence of corporate guilt becomes clearer as the apostolic mission spreads beyond the land of Israel, and Paul and his companions arrive in the town of Antioch in Pisidia, a district of Asia Minor. On Shabbat they join the synagogue service and are invited to bring a “word of exhortation for the people.” Paul rises to the occasion and tells the story of Yeshua’s coming as Messiah, within the familiar context of Israel’s history. Then he continues,

My brothers, you descendants of Abraham’s family, and others who fear God, to us the message of this salvation has been sent. Because the residents of Jerusalem and their leaders did not recognize him or understand the words of the prophets that are read every sabbath, they fulfilled those words by condemning him. Even though they found no cause for a sentence of death, they asked Pilate to have him killed. . . . But God raised him from the dead. . . . And we bring you the good news that what God promised to our ancestors he has fulfilled for us, their children, by raising Jesus; as also it is written in the second psalm,

‘You are my Son;

today I have begotten you.’ (Acts 13:26–28, 30, 32–33, emphasis added)

Note the change in terminology here, evidenced in the emphasized words and phrases. Earlier, when Peter spoke to the crowd in Jerusalem, he addressed those directly responsible for Messiah’s death as “you.”

This man, handed over to you according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of those outside the law. . . . Therefore let the entire house of Israel know with certainty that God has made him both Lord and Messiah, this Yeshua whom you crucified. (Acts 2:23, 36)

Here in Pisidian Antioch, Paul describes the very same people as “they,” namely, “the residents of Jerusalem and their leaders.” In Paul’s us-and-them terminology, “us” signifies Jews who are faithful, or at least open, to the prophetic message of Messiah’s appearing; “they” are Jews who cooperate with the gentiles (represented here by Pilate) in opposing it. Paul is not alleging a unique corporate Jewish guilt, any more than he is alleging a unique corporate Jewish faithfulness.

It’s important to note, however, that Israel, the Jewish people, do bear a unique standing in regard to the good news of Yeshua. Paul continues to attend the synagogue and proclaim the good news, not just here in Pisidian Antioch, but throughout his travels: upon arrival at Iconium (Acts 14:1); for three Shabbats in Thessalonica (Acts 17:2); upon arrival in Berea, where he’s warmly received at first (17:10–12); in Athens (Acts 17:17); in Corinth (18:4); and for three months in Ephesus (19:8), before setting out to return to Jerusalem. This pattern may be a reflection of the phrase “to the Jew first” in Romans 1, and like that phrase the pattern itself isn’t just a matter of itinerary or missionary tactics.15 The Jewish people retain a unique standing in the prophetic schema, and hence a unique accountability in their response to Yeshua, but it’s a gross oversimplification to state this standing simply as “the Jews killed Jesus.”

In our preceding passage, Acts 4:24–28, the apostles interpreted the first two verses of Psalm 2 as a prophecy of the Jewish-gentile collusion in the death of Messiah. Here in Acts 13 Paul cites a verse later in the psalm as a prophecy of the resurrection of Messiah: “You are my Son; / today I have begotten you.” Like Peter in Acts 2, Paul invokes the resurrection not only as the vindication of Yeshua’s status as Lord and Messiah, but also as essential to the fulfilment of God’s promises to the Jewish people. After Peter calls on “the entire house of Israel” to recognize Yeshua as Lord and Messiah, he continues, “For the promise is for you, for your children, and for all who are far away, everyone whom the Lord our God calls to him” (Acts 2:39). Likewise, Paul tells his fellow worshipers in the synagogue, “And we bring you the good news that what God promised to our ancestors he has fulfilled for us, their children, by raising Yeshua” (Acts 13:32–33a). Humankind responds to God’s Messiah by rejecting him and putting him to death; God has the final word, however, by raising Messiah from the dead and keeping his promises to Israel.

The apostles hold both Jews and Romans accountable for Messiah’s death, those Jews and Romans who actually “gathered together” in collusion with Herod and Pilate. Their verdict, however, bears a broader implication: Rome, the great gentile power, and Israel, the chosen nation among the nations, together represent all humankind, which shares responsibility for the death of Messiah. With an eye on Luke’s historical perspective, we might say that the great forces of human history—Israel and the nations—unite to resist God’s incursion onto the stage of history through his Messiah.

The idea of a unique and inherent Jewish culpability, then—reflected in the terminology “the Jews killed Jesus”—is both morally defective and untrue to the text of Scripture. In addition it shifts attention away from the focus of the apostolic message, which is the resurrection of Yeshua, foretold by the prophets and key to the fulfillment of all the promises the prophets convey. As we conclude this discussion therefore, we return to this focus on the resurrection itself.

Human Agency and Divine Necessity

In the final chapter of Luke, Yeshua joins two of his followers as they walk along a road in the hills of Judah on the third day after his crucifixion, but they don’t recognize him. He asks them why they look so downcast, and they tell him the story of Yeshua’s mighty deeds and words, ending with his arrest and crucifixion, the empty tomb, and their own disappointment at the outcome. Yeshua responds: “O foolish ones, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” (Luke 24:25–26). In this passage, “The verb of necessity (Greek: dei) refers to God’s divine plan of salvation.”16 The same verb appears in Yeshua’s first warning of his impending death: “The Son of Man must undergo great suffering, and be rejected by the elders, chief priests, and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised” (Luke 9:22, emphasis added). Soon after saying this, “he set his face to go to Jerusalem,” where all these events will take place, and he employs the “verb of necessity” again at critical moments in the journey to describe those events (Luke 9:51; 13:33; 17:25; 22:37, cf. 22:7).

The use of dei just before the journey to Jerusalem forms an inclusio with its use after the journey has been fulfilled in Messiah’s death and resurrection. Indeed, in Luke 24 Yeshua employs this verb three times; first on the road to Emmaus (vs. 26), and then twice in speaking to the eleven and their companions (including the two Emmaus road disciples; vss. 44–46).17 This three-fold usage creates a powerful conclusion to the entire narrative introduced in Luke 9:22.

The emphasis in this narrative is not human agency, but divine necessity, as implied in all three passages in Acts examined above. These three passages, which deal so explicitly with the historical forces at work in the execution of Messiah, also emphasize the divine necessity of his suffering and the resurrection that follows.18

- Acts 2:23. Peter tells his Jerusalem audience that “this man”—Yeshua—was “handed over to you according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God.”

- Acts 4:28.The friends of Peter and John pray to God, saying the Jewish and gentile authorities gathered together “to do what your hand and your plan had predestined to take place.”

- Acts 13:27. Paul tells the synagogue of Pisidian Antioch, “Because the residents of Jerusalem and their leaders did not recognize him or understand the words of the prophets that are read every sabbath, they fulfilled those words by condemning him.”

Yeshua told his two interlocutors on the way to Emmaus it was necessary for Messiah to suffer and enter into his glory. “Then, beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them the things about himself in all the scriptures” (Luke 24:27). Now “all the scriptures” do not speak explicitly of a suffering and resurrected Messiah.19 But they do speak of a compassionate God who meets humans in their weakness and suffering, identifies with them, and brings them through all adversity. Thus, after the incident of the golden calf, Moses prevails upon God to accompany Israel in the wilderness with his own presence (Exod 33:12–17). Then, in response to another request of Moses, God reveals himself fully as “a God merciful and gracious / slow to anger / and abounding in hesed—steadfast love,” in what Jewish teaching terms the Thirteen Attributes of Compassion (Exod 34:6–7). The Prophets and Psalms fill out this picture in numerous passages, in which God’s compassion leads him to be present with his people, perhaps most poignantly in Isaiah 63:9—“In all their troubles he was troubled.”20

The presence of a suffering Messiah is an inevitable outworking of the divine self-revelation as “God merciful and gracious.” It was necessary for Messiah to suffer not only to pay for our sins, but also to reveal who he is and thereby who God is—a God of mercy, who is so near that he suffers alongside his people. And when Messiah rises, it is also not only to advance the work of redemption, but to reveal himself more fully. In Acts, “Jesus’ resurrection points to who he is—the Holy One—and where he has gone—to share in the divine rule from the side of God.”21 These two components together, the vindication of Yeshua and his exaltation to the divine throne, help complete the portrayal of God himself.

Human powers and authorities resist God and his anointed one because it is in their nature to do so. Likewise, the Messiah must suffer in full identification with humankind because it is in his nature to do so. The focus on human agency in Messiah’s death must yield to a more profound drama: through Messiah’s death and resurrection, God identifies with us in our deepest sin and alienation and raises us up into life that overcomes all adversity. As it is written, “Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things and enter into his glory?”

Russ Resnik is a veteran rabbi, teacher, counselor, and writer, currently serving as Rabbinic Counsel of the Union of Messianic Jewish Congregations (UMJC). He has lectured throughout the USA and in Israel, Canada, Mexico, South America, South Africa, and Russia. Russ was ordained through the UMJC in 1990, and served as UMJC executive director from 1999 to 2016. He is the author of five books, including the upcoming Besorah: The Resurrection of Jerusalem and the Healing of a Fractured Gospel, co-authored with Mark Kinzer, and the editor of Kesher: A Journal of Messianic Judaism. Russ and his wife, Jane, have four children and seven grandchildren, and live in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

1 Mark Galli, “Killing Jesus’ Brothers and Sisters,” https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2020/january-web-only/killing-of-jesus-jewish-brothers-and-sisters.html. The original version was accessed 1/2/20.

2 Galli, “Killing Jesus’ Brothers and Sisters,” accessed 5/3/20.

3 Deborah E. Lipstadt, Antisemitism Here and Now (New York: Schocken, 2019), 17–18.

4 Galli, “Killing Jesus’ Brothers and Sisters.”

5 Amy-Jill Levine and Ben Witherington III, The Gospel of Luke (Cambridge University Press, 2018), 622–8; The Jewish Annotated New Testament, Second Edition, Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds. (Oxford University Press, 2017), 163.

6 Ben Witherington III, The Acts of the Apostles: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 21–24; Jewish Annotated New Testament, 219–220.

7 Witherington, Acts, 21 (emphasis in the original).

8 Unless otherwise noted, biblical references are from the NRSV, with occasional word substitutions, such as “Yeshua” for “Jesus” and “Messiah” for “Christ.”

9 Darrell L. Bock, “The Book of Acts and Jewish Evangelism,” in To the Jew First: The Case for Jewish Evangelism in Scripture and History, Darrell L. Bock and Mitch Glaser, eds. (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2008), 61.

10 Witherington, Acts, 141.

11 We are passing over Acts 3:12–26, another important sermon, which also addresses the issue of human agency in the death of Messiah. It focuses on Jewish agency, mentions Pilate in rather exculpatory terms, and the actual executioners not at all. The preceding and following chapters (sections 1 and 2 here) present a broader and more detailed picture of Jewish-Roman collusion in Messiah’s crucifixion.

12 Gerard Van Groningen, Messianic Revelation in the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1990), 337.

13 F. F. Bruce, Commentary on the Book of Acts (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970), 106.

14 Robert Alter, The Book of Psalms: A Translation with Commentary (New York: Norton, 2007), 5.

15 “Paul makes quite clear from the beginning that the order of God’s salvation for humankind is now, as it has certainly been in the past, ‘To the Jew first and also to the Greek’ (1:16; 2:9–10; 9:24; 15:8–9).” Mark D. Nanos, The Mystery of Romans: The Jewish Context of Paul’s Letter (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1996), 227.

16 Levine and Witherington, Luke, 662.

17 The word is also employed in Luke 24:7 by the “two men” who remind the women who have entered the empty tomb of Yeshua’s earlier prediction of his death and resurrection.

18 The second passage doesn’t speak directly of the resurrection, but records the evidence for it, the outpoured Spirit (cf. Acts 2:33–34), as Yeshua’s followers were again “filled with the Holy Spirit and spoke the word of God with boldness” (Acts 4:31).

19 Levine and Witherington, Luke, 662–3, 668.

20 NJPS translation; cf. ESV, NRSV margin. Other examples of God present in human suffering are Psalms 22 and 23; Isaiah 53:4, 57:15.

21 Bock, “Book of Acts,” 59.