Thriving, Not Just Surviving: Reconceiving Community for a Better Tomorrow

Rabbis Klayman and Nichol provide excellent retrospectives on Jewish communal stability amidst the crises of yesterday and today. They speak of past and present. In the current essay, however, my focus will be on community structures suited to a better tomorrow. Just as the quality of a building is determined by how well it serves a particular purpose, so we must ask what kind of community structures will best serve the people and purposes of tomorrow’s Messianic Judaism.

Rabbi Klayman highlights our extraordinary record of communal survival, a persistent trek through the ages, repeatedly adjusted to calamity and crisis. He illustrates this by examining Jewish communal response to three ancient calamities: the destruction of the First Temple, of the Second Temple, and the failure of the Bar Kochba Revolt, before detailing the Jewish response to the Spanish Flu pandemic of a century ago. Yes, despite every deadly obstacle we have faced, Am Yisrael Chai! The people of Israel live! Parsing the present, Rabbi Nichol provides a detailed analysis of how the Covid-19 pandemic impacted the Messianic Jewish congregational world, how our communities adjusted, how they were affected by the process, and how we survived.

As we look toward the future, survival will be as much a concern for us as it was in the past and continues to be in our day. Mere survival, however, cannot be our communal purpose. Survival is not a purpose but a precondition to being able to serve a purpose. We must set our sights beyond surviving to thriving. How should we reconceive and reconstruct our communal structures as habitations for a better tomorrow?

To address these issues, this essay will examine three questions:

1. What should characterize tomorrow’s Messianic Jewish communal life?

2. How effective have we been in implementing these communal markers?

3. What past and present structures should we renovate to shape a better tomorrow?

What Should Characterize Tomorrow’s Messianic Jewish

Communal Life?

Rabbi Rich takes us into the realm of communal context when referencing the authoritative work of Sherry Turkle of M.I.T. He wisely warns of the limitations and dangers of Zoom as an environment for communal culture. Rabbi Rich concurs with Turkle: “Zoom and other formats were a life-saver for Messianic Jewish synagogues during Covid, but imagining that virtual reality can replace flesh-and-blood connection would be a big mistake.”

But why are Zoom and other virtual formats inadequate as a communal base? Rabbi Rich quotes Turkle, “The ties we form through the Internet are not, in the end, the ties that bind. But they are the ties that preoccupy.”1 Nichol adds, “This observation is just too important to ignore if Messianic Judaism is to prosper.” In a time overshadowed by Covid, however, and also due to shifting preferences in meeting modalities, for the foreseeable future some congregations and havurot may occupy virtual space in whole or in part. The congregation I lead, Ahavat Zion in the Los Angeles area, is pursuing such a hybridized model. We see this ideally as a bridge to a better day of predominantly face-to-face meetings under one roof. Discerning why virtual reality is inadequate as a sustained meeting-environment takes us into the purposes which tomorrow’s communal structures will serve to be a proper habitation for a better tomorrow.

How will that look?

1. Being familial communities will characterize tomorrow’s Messianic Jewish communal life

Jay Y. Kim, a pastor in the San Francisco Bay area, addresses how virtual reality impedes spiritual community, contrasting this with a far better aspiration.

We live in an impatient, shallow, isolated culture. The idea of patiently journeying with a community of Jesus followers, doing the hard work of cultivating and excavating depth in our relationships with God and one another, and involving ourselves in the messy work of forging a meaningful community of diverse people doesn’t seem like an attractive option.

We must never lose our appetite for the real analog thing––true human connection and community, driven by empathy. Without it, discipleship to Jesus just isn’t possible.2

Without such empathy, we just do not have discipleship at all, but its chilly clinical sibling, indoctrination. Kim reminds us that our calling is something warmer than that, to develop believer-communities that embody and nurture familial relationship and connectedness. These are communities where everybody knows your name, where your wounds cause others pain, and their victories fuel your rejoicing. These are foundational and essential communal structures that actualize the familial bond intrinsic and essential to being the people of God together.

Joseph Hellerman takes us more deeply into what this means, exploring its roots and implications.

For Jesus, Paul, and early Church leaders throughout the Roman Empire, the preeminent model that defined the Christian Church was the strong-group Mediterranean family.

God was the Father of the community. Christians were brothers and sisters. The group came first over the aspirations and desires of the individual. Family values—ranging from intense emotional attachment to the sharing of material goods and to uncompromising family loyalty—determined the relational ethos of Christian behavior.3

We would do well to ask if this is community life as we know it, and if this description gives shape to the inchoate longings rumbling beneath the surface of the Messianic Jewish community, especially along the fissure line of the millennials among us.

In this model, the strongest relationship was that of being siblings joined to the same father through the same older brother. Of course, for the Yeshua-believing communities the Father was God, the elder brother, Yeshua. This model will be new to some of us, but it was the norm for the North Mediterranean family, upon which the early Yeshua believers based their communal structure. This model is biblically rooted, reflected in Second Temple Judaism, and was used and modified by Yeshua, Paul, and the early believers, while all being reflective of cultural assumptions in the Mediterranean area, what is known as a Patriarchal Kinship Group collectivist culture.

The basic building block of Jewish society was the bayit or beit av, which is best understood as a family household, extended or compound family. Your bayit is your multi-generational entourage, your posse, your web of familial and family-like relationships. This is why B’reisheet (Genesis) 14:14 says this when Avram went out to rescue Lot and the captives taken from the city of Sodom: “When Avram heard that his nephew had been taken captive, he led out his trained men, who had been born in his house (his bayit), 318 of them.”4 These were not his children. Neither Isaac nor Ishmael had yet been born. But these men were part of his bayit, his posse, his entourage, his encampment. This was the foundational structure of communal understanding for Yeshua and his disciples.5

In transplanting this model throughout the Roman world, Paul adapted it to Roman culture and its comparable communal model, the oikos. Consequently, in his letters, the following four family values predominate in Paul’s groups:

1. Affective solidarity: The emotional bond that Paul experienced among brothers and sisters in God’s family.

2. Family unity: The interpersonal harmony and absence of discord that Paul expected among brothers and sisters in God’s family.

3. Material Solidarity: The sharing of resources that Paul assumed would characterize relationships among brothers and sisters in God’s family.

4. Family loyalty: The undivided commitment to God’s group that was to mark the value system of brothers and sisters in God’s family.6

Very few of us have any experience with this level of familial spiritual engagement. We do well to mourn what we have lost: a treasure protected by prior generations, and one evident not only among Yeshua-believers, but others as well, including the Jewish world. Let me illustrate that for you.

I remember my grandmother’s funeral, some forty-seven years after her 1912 arrival in the United States. One of the attendees was a representative of her Landsmanshaft (“Countryman’s Association”), a social support society for immigrants from her locale in Europe. This man was a stranger to us, but he came to honor my grandmother as a representative of her communal connection to other Jews, especially those from her region in the Old Country. Hundreds of such societies formed the vital relational bridge without which establishing Jewish life in the New World could never have happened.

Ironically, these Jewish immigrant societies perfectly reflect the kind of communal commitment Hellerman insists is foundational to functioning Yeshua-communities. Note the intimate, familial, and whole-life support that characterized these groups:

The Landsmanshaft organizations aided immigrants’ transitions from Europe to America by providing social structure and support to those who arrived in the United States without the family networks and practical skills that had sustained them in Europe. Toward the end of the 19th and in the beginning of the 20th centuries, they provided immigrants help in learning English, finding a place to live and work, locating family and friends, and an introduction to participating in a democracy, through their own meetings and procedures such as voting on officers, holding debates on community issues, and paying dues to support the society. Through the first half of the 20th century, meetings were often conducted and minutes recorded in Yiddish, which was the language that all members could understand. . . .

Members paid dues on a regular basis, and if they lost their jobs, became too sick to work, or died, the society paid the member or their family a benefit to keep them afloat during that time.7

While these associations present an additional example of Rabbi Klayman’s collection of Jewish responses to crisis and stress, we must not imagine that such sinewed support structures were exceptional, born out of the urgency of the immigrational moment. No. These kinds of practical associations for communal support honeycombed and supported Jewish community for thousands of years.

Israel Goldman fascinates us, portraying the warp and woof of a communal life that largely, but not entirely, went up the chimneys of the Shoah. Notice again the intimacy and practicality of Jewish communal association at its best.

In every Jewish community in past ages, the hevrah—a duly constituted society for the promotion of certain specific occupational, charitable, religious, or educational purposes—was the most significant unit of voluntary association. Hevrot were founded wherever there were Jews, each of these confraternities bearing the appellation “kaddisha,” for each group was a sacred society or holy brotherhood. . . .

How the holy brotherhoods originated is hard to tell. . . . There is every likelihood that the holy brotherhoods of later centuries had their prototype in talmudic times. It is also very likely that similar types of associations existed in Palestine and Babylon before 500 CE . . .

Their greatest development came in the eighteenth century, and many were centered in the Jewish proletariat. The Jewish working classes formed hevrot in accordance with their various occupations. Since most societies also established their own places of worship, it is noteworthy that in Vilna there were nearly one hundred small synagogues named for the occupations of their members. Thus were the conventicles, or klausen of the bakers, the carpenters, the tailors, the leather-workers, the shoemakers, the weavers, the glaziers, the bookbinders, and the tinsmiths.

The holy brotherhoods came into being mainly to serve the economic and religious needs of their members. Christian workingmen had their own craft guilds, and Jewish workingmen found it necessary to organize similar societies for their own economic protection and betterment as well as for mutual aid.8

Community is not just a concept, an abstract ideal. Truly human spiritual community will be irreducibly intimate, practical, accountable, and familial, having social structures that support and sustain the community and its members.

Therefore, if they are to truly be gatherings of God’s family rather than collections of his fans, our communities will be face-to-face familial gatherings of mutual accountability and concern.

2. Being communities of empowered Messianic Judaism will characterize tomorrow’s Messianic Jewish communal life

We welcome to our discussion table Rabbi Elie Kaunfer, visionary leader of the Independent Minyan Movement, representing what has come to be known as Empowered Judaism. Although Messianic Jews commonly claim spiritual empowerment through the gift of the Spirit and the Messiah’s ascension gifts, if we are to fully be an Empowered Messianic Judaism, we would do well to listen to what Rabbi Kaunfer has to say.

The son of a pulpit rabbi, Elie Kaunfer never planned to become a rabbi himself but changed direction to better pursue his passion for a prayer-based egalitarian community of millennials who, like himself, seek a Jewish life filled with satisfactions Judaism is meant to supply.

He and the other founders of the Independent Minyan Movement would not settle for what Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel termed “religious behaviorism,” mere formalistic compliance with Judaism’s demands.9 Their alternative is what they term Empowered Judaism, which first found expression through their founding a minyan (liturgical-prayer quorum) that met first in a series of apartments, and later in whatever suitable rental facilities that could be found and afforded in Manhattan. For those needing further explanation, the website My Jewish Learning helpfully explains:

Minyan is the Hebrew word that describes the quorum of ten Jewish adults required for certain religious obligations. The word itself comes from the Hebrew root maneh (מנה) meaning to count or to number.

One can always say one’s prayers by oneself, at any time or place, but praying with others brings a sense of connection and closeness, and can strengthen the collective to focus on their prayers more deeply. By requiring a minyan for many fundamental rituals, Judaism encourages communal cohesion.10

Kaunfer’s egalitarian minyan became known as Kehilat Hadar. From this effort grew a movement of similar gatherings, Independent Minyanim, scattered across the USA and in Israel.

The movement has grown chiefly among Jews in their twenties and thirties, and mostly in coastal urban areas of extensive Jewish population. Empowered Judaism is a vision serious about Jewish observance, loyal to tradition, and insistently egalitarian. The movement represents a shift from more common motivations driving Jewish community concern for millennials. As in the Messianic Jewish world, those standard motivations include a concern for communal preservation, for preservation of communal institutions, and for combatting the communal decay attendant upon intermarriage and secularism. For Kaunfer and friends these motivations are not enough. Neither should they be enough for Messianic Jews.

Going beyond these pragmatic motivations, Empowered Judaism pursues an egalitarian and communal vision of equipping and assisting average Jews to meaningfully and skillfully pursue a robust engagement with the texts, behaviors, and satisfactions of Jewish life. This vision insists that such skills and satisfactions must not be left to elite experts and academics. This is a rich Judaism for everyone else. To the surprise of many, it is taking hold, especially among singles in their twenties and thirties.

Unlike the havurah movement of the late sixties and early seventies, Empowered Judaism is not so much a protest against institutionalism as a complementary modality meeting needs and serving a public under-served by standard Jewish community structures. While independent minyanim are non-denominational and egalitarian, they are not pluralistic. They hold to a robust and rigorous understanding of the nature of Jewish prayer and practice. For example, they insist on praying liturgical services in their entirety, including prescribed repetitions, and also insist that this be done skillfully, in a manner meaningful for all. While others said it couldn’t be done, Empowered Judaism said it must be done, and is doing it.

Kehilat Hadar birthed the Hadar Institute, which Kaunfer now directs, and Yeshivat Hadar, the first egalitarian yeshiva in the west. It offers a kind of boot camp approach to teaching textual skills while modeling religious Jewish ways of thought and discussion for their mostly millennial constituents. Admission to the program is on a competitive basis, as they want students who are able and eager to work hard before transplanting among others the ethos and substance of the movement. Students at the yeshiva are subsidized, which is another reason for an application process. It is a different kind of yeshiva, not concerned with raising up a cadre of Jewish professionals, rabbis, cantors, and education directors. Instead it seeks to empower Jews to learn, to love, and to live Jewish life. You might call it “a yeshiva for the rest of us.”

What does all of this have to do with having an Empowered Messianic Judaism, or more precisely, Empowered Messianic Jews? Everything.

About Being Empowered

Some will protest, “But we already have an Empowered Messianic Judaism! We have the Spirit sent by Messiah!” Fair enough. But while we lay claim to the empowering Spirit, to what extent is this a mere position statement long on explanation and short on demonstration? And to what extent do claimants seek to legitimize this claim in culturally derivative ways (hands in the air, speaking in tongues, falling over for example), markers that alienate the Jewish world of which we claim to be a part and to whom we are especially called. It is both fair and essential to ask in what ways our communities and people embody an Empowered Messianic Judaism where each word in the label is demonstrated Jewishly, and relevantly.

About Being Messianic

What about the middle word in the phrase Empowered Messianic Judaism, Messianic, and the markers with which it is properly associated? Can we attest that the majority of our people are biblically knowledgeable, with established habits of ever-deepening immersion in our holy texts? What percentage of our people are scripturally adept? Are we as leaders equipped to lead our congregants into such a robust engagement with Scripture? What of convictions about Messiah? Do all of our community members go beyond seeing Yeshua as rabbi and sin-bearer, to seeing him as Risen Lord, coming Judge, and Second Person of the Triune Godhead? What do our people think about Yeshua? Can they derive and defend their views from Scripture and relate them intelligently and respectfully to the history of discussion of these matters? After half a century in such circles, my answer to all of these questions is, “In most cases, probably not.”

About Being a Judaism

As for the third term in Empowered Messianic Judaism, what of the texts of our tradition, the record of thousands of years of Jewish communal processing of holy responsibility and privilege? Are such texts unknown, unexamined, and untrusted in our midst? In many cases, yes. Are our people equipped and motivated to think Jewishly, to live Jewishly, to pray Jewishly while at the same time always giving honor to the Father through properly honoring the Son? Or is ours a movement too often either of Jewish minimalism (at best), or of Jewish affectation? I remember going to a Messianic regional conference many years ago where a family member suggested what we had encountered there was “Appalachia meets Fiddler on the Roof.” We have to do better than this if we are to claim to practice and commend an Empowered Messianic Judaism. If our Judaism is trivial, why are we surprised so few Jews want it?

We need to work toward becoming familial communities empowered in Jewish prayer, learning, and practice, filled with the Spirit, extending the Presence of Yeshua in the world through incarnating his Presence in how we relate to all. And while it would be best if Messianic Jewish leaders and congregations could agree on on what we are uniquely called to be and to do as custodians of today’s and tomorrow’s Messianic Judaism, even if we cannot agree, as many of us as possible must expend the effort and make the sacrifices necessary to make the vision of a truly empowered, truly Messianic, and truly Jewish Empowered Messianic Judaism a reality in the lives of our people as a beacon to all Israel.

This is the purpose for which we must discover and implement appropriate communal structures. And this brings us to a third characteristic of a desirable Messianic Jewish tomorrow.

3. Being financially viable but not financially-driven will characterize tomorrow’s Messianic Jewish communal life

Thanks to Covid-19 we now know how vulnerable we are in a multitude of ways, including matters of income. Thankfully, most congregations did not lose their meeting places, although I know of at least one that did. Nevertheless, we experienced the precariousness of our position. Whether through pressures of politics, persecution, or pandemic, our standards of living and ways of congregating are vulnerable. The times are challenging us to examine where and how we need to dig in, and where and how we need to seriously consider making changes. What we need is a strategy for adaptable, flexible stability.

Financial Viability in Stressful Times

The experience of European Christians who resisted and suffered under Communism has much to teach us about communal viability and adjustment during times of change, pressure, and even persecution. Christian author Rod Dreher conducted interviews with survivors of the rigors of Soviet religious repression, among them Baptist Pastor Yuri Sipko, whose experiences were surely more severe than anything we are apt to face. Notice what he says about the connection between marginalization, ideological warfare, persecution, and financial instability:

To be a Baptist in Soviet Russia was to know that you were a permanent outsider. They endured it because they knew that truth was embodied in Jesus Christ, and that to live apart from him would mean living a lie. For the Baptists, to compromise with lies for the sake of a peaceful life is to bend at the knee to death. “When I think about the past, and how our brothers were sent to prison and never returned, I’m sure that this is the kind of certainty they had,” says the old pastor. “They lost any kind of status. They were mocked and ridiculed in society. Sometimes they even lost their children. Just because they were Baptists, the state was willing to take away their kids and send them to orphanages. These believers were unable to find jobs. Their children were not able to enter universities. And still, they believed.” The Baptists stood alone, but stand they did.11

Pressure, tumult, change, and crisis attack financial stability. Even though we cannot know what kinds of crises await us, nor their intensity, we will better sustain communal continuity if we implement communal structures that remain financially viable in changing times.

On Not Being Financially-Driven

There is another, more insidious financial destabilizer that threatens to destroy our freedom, faith, and communal stability. It is all the more dangerous because for the most part it lies undetected, perfectly blending in with our cultural assumptions. The destabilizer is our de facto attraction to bigger-is-better ministry models. Who would deny that the mentality within our ranks is that the largest congregation is the most successful, and that having a beautiful building that is all our own and a fat budget is the path to fame within the Messianic Jewish ranks? But where are we told that this should be our measure of success? This seems to be more business than Bible. Getting rich this way exacts a price we should avoid paying.

There are many insidious ways this works against communal well-being. For example, with this mentality, when people seek to start a congregation, the first two questions are not visionary or missiological; they are financial. How are we going to pay the rabbi? How are we going to pay the rent (or the lease)? Addressing these issues becomes an organizational priority from day one and remains so from then on. And as in the case of the Independent Minyan movement, being in the business of building Jewish community puts us in major coastal urban areas where expenses are high.

With a bigger-is-better mindset, whatever increases congregational income is good, and whatever threatens it or fails to contribute to financial well-being is deemed bad. While the financial tail is not meant to wag the missional, congregational dog, often it does just that. Our reaching other Jews and incorporating them into a warmly familial faith community should drive our agenda, and our budget should serve that purpose. But when finances become the bottleneck, then whatever increases and does not impair income, controls the agenda. This is not a flattering picture. But the face in the portrait is our own. This is what is termed, “the golden handcuffs.”12

I like financial sustainability and financial success as much as anyone. But whenever or wherever building spiritual familial communities and enfolding Jewish people into Yeshua faith takes a back seat in decision-making to bigger-is-better fiscal planning, something is wrong. There is a difference between being in the Lord’s business and being in the Lord business. We should be financially viable but not financially-driven communities.

What we need is a low cost, flexible, sturdy and stable ministry model. And yes, there is such a thing to be unpacked later.

How Effective Have We Been in Implementing These Communal Markers?

We just completed what should characterize tomorrow’s Messianic Jewish communal life, identifying three characteristics: We will be familial communities, we will embody an Empowered and Empowering Messianic Judaism, and our communities will be financially-viable but not financially-driven. As we look toward the future, how effectively have we implemented these markers in our current context?

How Well Have We Developed Familial Communities?

Yeshua said of himself as the Good Shepherd, “He calls his own sheep, each one by name, and leads them out.” It’s a wonderful thing when we meet leaders who know all their congregants by name! I know congregational leaders for whom this is absolutely so. But will you agree that this is not always the case? And what about our congregants and their relationships with each other? Do our congregants have face-to-face relationships with each other such that they know each other’s names, lives, pains, joys, gifts, and challenges, or is this only true of certain groups and cliques?

Is the problem that our shepherds do not care for the sheep? God forbid! Rather, the problem is one of structure. Our meeting models work against intimate familial relationships.

More often than not, Messianic Jewish communities are meeting-based, practicing a kind of weekend spirituality centered in the Big Meeting. This is “spectator spirituality.” The congregation meets in a big room where there is a platform which is really a stage, a worship team which is a band, an inspirational speaker, hopefully with excellent visual aids, called the Rabbi, and a congregation which is an audience. Many people labor hard and long with considerable skill to maximize the quality and impact of such events. But we need to ask ourselves if the people who attend week by week are really being enfolded into face-to-face familial relationships, equipped and empowered as practitioners and advocates of empowering and Empowered Messianic Judaism, in relationships of mutual accountability. In too many cases this is not happening. We may be working hard, but our structures are working against us.13

How Well Have We Equipped Our People for Empowered Messianic Judaism?

Are we successful in doing this job if, after decades as Yeshua-believers, our people are not themselves proficient in handling the Word of truth and in passing on to others the life we have been given, especially to Jewish people? Are they equipped to embody and to pass on to others an Empowered Messianic Judaism? Have we equipped our people for this when our community life and family lives fail to reflect the texture of Jewish spirituality, where our manner of speaking and living might be termed Kenneth Copeland with a Kippa? Should we not be a living and vital communal link between the Jewish generations past and the generations to come? When the only response many congregants have to the inquiries of Jewish friends is, “You’ll have to come to one of our services,” or, “You really need to meet our Rabbi,” because they know themselves to be superficial or ill-equipped in discussing their life of faith, then we need to ask if this is the kind of communal life that turned the world upside down. We need to do better, we want to do better, and we can do better.

Dependency is one of the problems that gets in the way. If our systems work to maintain our people’s dependency upon their leaders then aren’t we failing to empower our people? In contrast, the Empowered Judaism of the Independent Minyan movement sought to replace dependence on a leadership class with developing deep proficiency in the laity. Can we do any less? An Empowered Messianic Judaism will bear in mind what the Apostle Paul called for when, writing to the Ephesians, he said of the risen Messiah, Israel’s Shepherd-King:

He gave some people as emissaries, some as prophets, some as proclaimers of the Good News, and some as shepherds and teachers. Their task is to equip God’s people for the work of service that builds the body of the Messiah, until we all arrive at the unity implied by trusting and knowing the Son of God, at full manhood, at the standard of maturity set by the Messiah’s perfection. (Eph 4:11–13)

If our task is “to equip God’s people for the work of service that builds up the body of Messiah,” then our leadership task is to work ourselves out of a job rather than perpetuating dependency. That is something to shoot for, isn’t it?

How Well Have We Developed Financially-Viable But Not Financially-Driven Communities?

Each of us will have to answer this question for ourselves. How much has our decision-making and our programming been determined by the need to maintain a positive cash-flow? To what extent are our leadership headaches and heartaches about touching people’s lives with the powers of the Age to Come, while enfolding them into the kind of rich and familial Empowered Messianic Judaism described here? On the other hand, to what extent do financial heartaches and headaches overshadow our deliberations? I agree these are not either/or matters. We need to be concerned both about people and about finances. But we need to ask, what looms large? Is the budget the crux of every board meeting, and what keeps us up at night? Or are we like the Apostle Paul who reported, “I have toiled and endured hardship, often not had enough sleep, been hungry and thirsty, frequently gone without food, been cold and naked. And besides these external matters, there is the daily pressure of my anxious concern for all the congregations” (2 Cor 11:27–29). His preoccupation was the condition of the flock, not the dimensions of the sheep pen.

Paul’s was a multiplication strategy producing financially viable interdependent familial communities, rather than an addition strategy implementing a business growth philosophy where bigger was always better. If our persistent anxieties are financial, and if financial pressures drive our programming, then something is wrong. Laboring for the kingdom is one thing: burning out for the budget is something else entirely.

Rabbi Rich’s respondents reported that financial pressure did not increase during Covid-19 partly because the pandemic decreased expenses. Lower expenses mean less stress. But the bigger-is-better mentality not only subjects us to continual pressure, it also skews goals and activities toward achieving and maintaining a financial bottom line, and one that we seek to expand if at all possible..

There must be a better way by which to multiply people served without increasing financial burdens. Fortunately, a model for doing this is hiding in plain sight. This brings us to our third main issue.

What Structures Should We Renovate to Aid Us in Shaping

a Better Tomorrow?

At best, doing things the way we have always done them will mean getting the results we have gotten so far. However, our world is changing, as it always has. And with the advent of Covid-19, we are facing greater unpredictability and instability. If we do not change with our changing world, even ahead of it, we will not remain in place. We will fall behind.

Thus far we have considered three purposes that should characterize Messianic Jewish communal life: (1) forming familial communities, which will (2) nurture an empowered Messianic Judaism in (3) a financially-viable but not financially-driven manner. We turn now to considering communal structures to best serve these ends in tomorrow’s Messianic Judaism. This will require defining or redefining the following terms:

1. the modality and the sodality;

2. the havurah;

3. the 5-fold model as a Body Health Maintenance Team;

4. elders;

5. the 5Cs congregation;

6. the rabbi;

7. support structures such as the Union, MJTI, and the MJRC;

8. the Inverted Pyramid of Messianic Judaism.

Throughout we should keep in mind Paul’s words in First Corinthians, Chapter Three, where he reminds us that communal growth is both organic and organizational, not either/or, but both/and. First, the organic:

I planted the seed, and Apollos watered it, but it was God who made it grow. So neither the planter nor the waterer is anything, only God who makes things grow—planter and waterer are the same. However, each will be rewarded according to his work. (1 Cor 3:6–8.

God’s communities have life in themselves. They grow like seeds that have been planted, and like plants that must be tended. But Paul insists on organizational factors as well, saying, “For we are God’s co-workers; you are God’s field, God’s building. Using the grace God gave me, I laid a foundation, like a skilled master-builder; and another man is building on it. But let each one be careful how he builds” (1 Cor 3:9–10). God’s communities grow through God-implanted organic factors, but also through organizational skill and competence, including elements of structural design.

Organic growth devoid of organizational competence guarantees an unweeded garden. And where organizational structures and agendas dominate, they often strangle or trample the life they should be nurturing.

Let’s heed this warning about balancing organic and organizational factors as we define terms crucial to our better tomorrow.

The Modality and the Sodality

In August 1973, speaking at the All-Asia Mission Consultation in Seoul, Korea,14 Missiologist Ralph Winter challenged worldwide mission and church leaders engaged in strategic planning. He highlighted how the Christian movement has always progressed by employing two structures which he termed the modality and the sodality.

Winter defined the modality as the communal base of the people of God, which we commonly term the congregation, and pictured it as existing for the growth and maintenance of the people of God. The modality is essentially pastoral in focus. Winter’s modality is the local church or congregation with a hierarchy and vertical structure that has people of all ages and stages of life intersecting at various levels. Some people are highly committed, while others, due to life stages, beliefs, and choice, are nominally involved.

What then is a sodality? A sodality is a group comprised of those people in religious communities who join together to embrace an additional calling, seeking to expand the kingdom of God by focusing on a missional or pastoral task or commitment. Roman Catholic orders, with their various charisms and vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience are each sodalities. So are mission societies like Jews for Jesus, Chosen People Ministries, Food for the Hungry, and World Vision. And so are the various teams of emissaries sent out by Chabad-Lubavitch, who, like the Blues Brothers, see themselves as being on a mission from God.

Winter termed sodalities and modalities “the two structures of God’s redemptive mission.” Understanding how this works out in our context leads us to the havurah.

The Havurah

The problem with talking about havurot is that people assume they know what a havurah is. The term has been widely used for all sorts of small groups, with all sorts of purposes, in all sorts of settings. Such fuzzy, broad definitions won’t help us identify and develop structures for a better Messianic Jewish future. We need to get specific.

For our purposes, and for the Messianic Jewish future we envision, a havurah is a household gathering where people eat together, pray together, learn together, and grow in their life with God together for the sake of others. Such meetings are familial rather than formal, but they do not need to be consanguinal. They are people of the same immediate family, but are generally fictive, that is, those who share relational ties for which familial relational terms may properly be used by extension. This is what we find in the gatherings of the early Yeshua movement, from apostolic times until the fourth century. This aligns perfectly with our first proposed characteristic of tomorrow’s Messianic Judaism “being familial communities.”

What might be the optimal size of such a group? Andrew Mason, founder of SmallGroupChurches.com, advises that such groups should consist of a minimum of six and an absolute maximum of fifteen participants. Why these limits? Any group smaller than six intimidates the introverts who at first may simply want to observe. Groups smaller than six leave introverts feeling too exposed. A group larger than fifteen creates the opposite problem, making it difficult for people to break in and stay engaged. Unless they have dominant personalities, they are forced to the margins and become spectators.15

We might term the six-person minimum the participation floor, and the fifteen member limit, the participation ceiling. It is between this floor and this ceiling that the life of the havurah happens, this familial household gathering where people eat together, pray together, learn together, and grow in their life with God together for the sake of others, us nurtured. Of course in the Jewish context, these groups will be foundationally comprised of Jews and their family members, although others may participate as well.

One of the ongoing benefits of a havurah-based community is its financial viability. When one establishes a synagogue, the first questions are, “How are we going to pay the rabbi? How are we going to pay for our facility?” As I survey people about the havurah model and ask, “What is the chief expense of a havurah?” they all answer the same way: “The price of a meal.” And when that meal is pot-luck, we are talking about an infinitely sustainable model, financially-viable, but not financially-driven.

Havurot are meant to grow, but how? As the size of the group approaches or exceeds the participation ceiling such groups will reproduce themselves through birthing from within the group a new nucleus for another like group. This is one of the key insights for the better Messianic Judaism of the future: The Kingdom of God grows not by addition but by multiplication. Consequently, our goal should be to develop clusters of these self-replicating havurot. As they replicate, a wide web will develop, constituting a wider community

A central conviction of this essay is that Kingdom growth is grassroots growth, and is organic, not organizational. Rather than trickling down from the top of the organizational ladder, Kingdom growth arises organically from the activity of the Spirit in the microcosm. Yeshua emphasized this repeatedly, as in the metaphors of the mustard seed, the leaven, and the farmer whose crop grows, he knows not how.16

This being the case, a second conviction of this essay is that the value and contributions of higher organizational structures depends upon how well they serve grassroots developments. As a tree grows from the roots up, and as forests spread as trees multiply themselves, so with the Messianic Jewish Movement. The grassroots structures do not exist to serve the higher governmental and educational structures; those higher structures exist to serve the grassroots.

One of the structures serving the havurot at the grassroots level is the Five Fold Model seen as a Body Health Maintenance Team.

The Five-Fold Model as a Body Health Maintenance Team

Winter’s model of the modality and sodality is good as far as it goes. However, he fails to develop one scripturally-attested aspect of the sodality structure essential to the progress of God’s Kingdom among us. For Paul and his team members, sodalities were not simply engaged in congregation planting. They were engaged in maintaining congregational health. We might term such a function as serving as a Body Health Maintenance Team” (BHMT).

Like a multi-specialty medical health group practice, the members of a BHMT will be people with apostolic, prophetic, evangelistic, shepherding, and teaching gifts and skills. They are specialists and consultants whose goal is to train and monitor members of our social groupings, raising up people who embody one or more of these five Body health functions, by cooperating synergistically in the local context. Paul says that this is the way the Body builds itself up together in love (Eph 4:16). The specialists in the BHMT do not perform these functions for the local havurah communities. To do so would lead to a disempowering dependency relationship. Instead, team members identify and raise up, train, and monitor others within our modalities who, due to gifting and personality they view to be divinely chosen to themselves perform these functions. When these systems are working in harmony, “the whole body is being fitted and held together by the support of every joint, with each part working to fulfill its function; this is how the body grows and builds itself up in love” (Eph 4:16).

A word of caution is in order. When used as nouns, the terms apostle, prophet, evangelist, shepherd, and teacher connote hierarchical offices. Too often, these terms tend to segment the Body of Messiah, reserving certain functions for communal luminaries while leaving the rest of the community underutilized and underdeveloped, even if fed and led. We need to be careful about replicating the kind of clergy-laity division which too often results in congregant-passivity. We want to maximize Body involvement, and thereby, Body strength.

Missiologist Alan Hirsch helps us here. He urges that we subject these terms to a process of “verbification” or functional conversion, turning nouns into verbs: “apostling, propheting, evangelizing, shepherding, and teaching.” We might term this “the democratization of the five-fold model,” seeing it as distributed throughout the Body rather than reserved for an elite class.

Alan Hirsch provides a detailed analysis of these five body functions in his book, 5Q: Reactivating the Original Intelligence and Capacity of the Body of Christ.17 For our current purposes, we might characterize these functions as follows:

- Apostling persons embody a God-given holistic sense of a particular group’s calling. Such persons are a living and proleptic embodiment of the vision. They are the architects and builders of the community.

- Propheting persons are visionary intuitives, functioning as the group’s conscience. They have a passionate God-connection, and speak forth necessary words about the group and its responses to God’s will, telling the group what it needs to hear. This is not meant to be a grandiose role, but rather a servant function.

- Evangelizing persons are good news magnets, adept and gifted at winning a hearing, inspiring trust, and encouraging inquiries to embrace the risk of commitment to Messiah Yeshua. They are creative and adept at appropriately communicating the good news of the Kingdom.

- Shepherding persons are the watchful protectors of the community. They have an early-alert system about finding wandering sheep, concerned about tending their wounds and seeing that they are fed. These are the first people to notice when someone is missing from a regularly attended meeting.

- God-given teaching happens among people who are trustworthy explainers, able to give structured, understandable, retainable, practical, and God-honoring expositions of the truth of God.

Elders

Many would be surprised to know that it was elders, and not pastors, who were the default authority figures in the early Yeshua movement. Wolfang Simson succinctly outlines their function, couching his comments in the house church model he champions:

The house churches are led by elders, whose function is to father or mother the church. They bring redeemed wisdom to the church, overseeing the flock like a father overseeing his children, showing them how to live, and they add authenticity through a proven family track record and balanced and mature lifestyle.18

As we have seen, the people of God are intrinsically familial. Each havurah is an extended family within the wider family of God. Since this is true, it is altogether proper that elders are figures in the community who have a certain parental gravitas and function. They reflect the authority of God and of scripture not only in what they say, but in how they live.

The 5C’s Congregation

Examine the New Testament and you will find not two structures, Winter’s modalities and sodalities, but three. We find the home groups, and also sodalities, teams or groups of people sent out on a mission from God, a commitment beyond their home-group foundation. But there are at least two expressions of a third model, which we will call a 5Cs Meeting, represented by the Jerusalem Temple, and its surrogate, the synagogue. As community structures, the small home groups constitute the essential communal foundation, and the larger synagogue or Temple meetings served broader communal purposes.19

The five Cs are the essential and supplemental communal functions performed by these New Testament larger structures, meriting refurbishment in our day in the cause of a better tomorrow for Messianic Judaism. Here are those 5C functions:

- Connection – Linkage to a wider tradition and community across time. This includes rites of passage, rituals, Holy Days, and the learning legacy of Jewish life as viewed through the eyes of our Yeshua faith, in respectful interaction with the legacy of the ekklesia from among the nations.

- Celebration – Of God and his mighty acts.

- Catalysis – Energizing and focusing participants to commit to and serve communal core values and purposes.

- Communal Prayer – Gathering together to seek God’s face and to worship him.

- Children – A context where the next generation will see that the spirituality of their home has a wider communal context.

In the New Testament, all of these functions were performed by the Temple or synagogue.20 In our context, we will also have synagogues, likely hub synagogues, that are the staging area for such functions, populated by the havurah communities that constitute the localized clusters, or more broadly, webs of havurot. Those synagogues are best which best serve the needs of these havurah communities within a bottom-up vision for growth and development.

The Rabbi

Does this envisioned Messianic Jewish future have a place for rabbis? Of course it does! But in what capacity? To answer this question I recall a private conversation with a rabbi friend who has trained rabbis in the wider Jewish world for half a century. He remarked that the role of rabbis in our day is not so much to answer all questions, but to be the consultant who tells people where they might find their answers. In this sense then, the rabbi of the Messianic Jewish future will best be understood as a specialist, mentor, and consultant. As specialists, these rabbis will need to be trained in mastering and accessing the lore of Judaism, communally processed in respectful interaction with the wisdom of the Spirit mediated through the ekklesia from among the nations. As mentors they will need to go beyond shaping Jewish minds to shaping Jewish souls. And as consultants, they will need to know how to advise our people on matters of life, faith, and practice. And of course, rabbis will always be teachers. As we have seen, however, their teaching should equip their people for an Empowered Messianic Judaism, rather than developing a dependent relationship that makes the laity to be passive receptors of services rendered.

My research on the nature of the rabbinic role, and how its various aspects evolved from the role of priests and Levites from biblical times to the present, shows that a rabbi performs sixteen functions traceable to the priests and Levites. Such a rabbi:

1. Serves as a custodian of Israel’s revelation and traditions.

2. Teaches Israel the ways of God as embodied in the revelation and traditions.

3. Models fidelity to God, the revelation, and the traditions.

4. Advises the community on matters of ritual life.

5. Acts as a judge in disputes.

6. Coordinates financial and logistical matters pertaining to the community.

7. Facilitates the community’s worship of God.

8. Expedites rites of passage.

9. Seeks to insure that the presence of God continues to abide with the community and its members, by serving as a spiritual director, coach, and mentor.

10. Helps the community and its members when life is disrupted (as by crisis, sin, or disease). This is the counseling and healing function of the rabbi.

11. Is a catalyst in outreach.

12. Serves as a spokesperson for the congregation, the Jewish people, and Judaism to the outside world.

13. Speaks blessing and strength to the congregation and its members from the symbolic exemplar aspect of the rabbinic role.

14. Offers to God prayers as service of the heart, if necessary offers his/her life for the sanctification of the Divine Name, and presents his/her holy studies as a surrogate priestly sacrifice.

15. Intercedes for himself/herself, his/her family, for his/her congregation, the people of Israel, the nations, and the cosmos as an agent in the divine consummation of all things.

16. Leads his/her congregation.21

We can see that these functions will each find a role within the 5Cs model, and within Body Health Maintenance Teams, havurot, and Empowered Messianic Judaism. To train these rabbis as specialists, mentors, and consultants will require supplementing the standard classroom context with a more intimate communal model, where educators of rabbis will themselves function as specialists, mentors, and consultants. Ideally this would be one on one, or in small groups, preferably face to face, but also on-line.

Yes, we will need rabbis, not as superstars to whom congregants point with admiration, but as those who help to equip the Body of Messiah to live out and pass on an Empowered Messianic Judaism.

Support Structures

We will continue to need such institutions such as the Union, educational institutions, and the Messianic Jewish Rabbinical Council. But they, together with the havurah communities, and synagogues they serve, will need to consider a new paradigm of self-understanding that is bottom-up and not top-down. The higher up institutions will always be asking and answering, “How can we bring benefit to the people at the grassroots?” Of course this is neither a new question, nor one that is not regularly asked and answered. However, until now havurot had been regarded as break-out groups, supplemental to the synagogue life of the community, and optional. I am suggesting this understanding is in error. These familial groupings are ground zero for Messianic Jewish spiritual and relational maturation and multiplication; they are foundational, and it is only by attending properly to the foundation that higher levels of structural life can be justified and maintained.

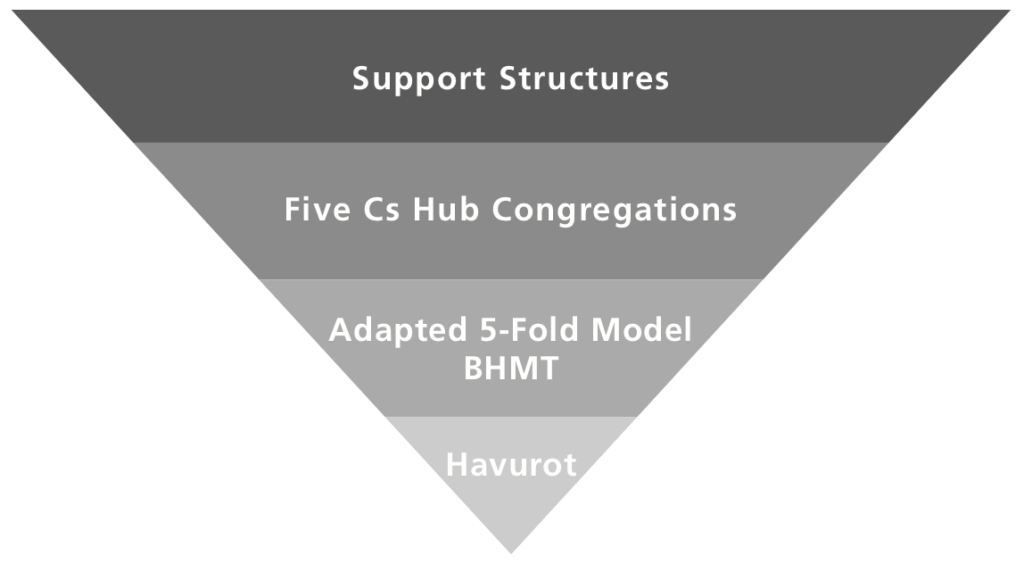

The Messianic Jewish Inverted Pyramid

The Messianic Jewish Inverted Pyramid portrays one principle underlying this essay, namely that the smallest group, the havurah, should be the focus of the most attention. The Kingdom of God grows organically, from the grassroots, or not at all, and the structures higher up the hierarchical ladder exist to nourish and sustain life and growth at the grassroots level. The question to be asked and answered by all levels of the community is this: How can we help our havurot to flourish and multiply?

For simplicity, the diagram includes but does not name all structural details mentioned in this essay. Also, particulars that must be worked out later have been left unmapped because such questions will need to be identified and resolved amidst the on-the-ground realities facing practitioners of tomorrow’s Messianic Judaism.

Where Shall We Go from Here?

We have accomplished what we set out to do, having examined what should characterize tomorrow’s Messianic Jewish communal life, our effectiveness in implementing these communal markers, and finally, how we might reconceive our community structures to shape a better tomorrow.

At the heart of our considerations is that growth is from the ground up. Therefore, prioritizing and multiplying smaller, familial, spiritual gatherings holds tremendous promise for building a thriving community for the future.

As is so often the case among our people, this brings us back to Torah, where we learn that it is at the microcosmic center, the Holy of Holies, that holiness and spiritual and societal well-being are most concentrated. From here these radiate into the community of the people of God and the wider world. This reminds us of the Mishkan (Tabernacle) and of the First and Second Temples, each termed a Beit Mikdash, meaning “Holy House.” In Jewish life the home is regarded as a mikdash m’at, a little sanctuary. This remains the Holy of Holies from which spiritual identity and vitality radiates into the world and daily life.

Perhaps, after reading this, you will agree that it is time for us to go home again to that center from which “Adonai will guard our going out and our coming in from now on and forever” (Psa 122:8). Kein y’hi ratzon. May such be God’s will!

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann, PhD, is a teacher and writer whose contributions include The Rabbi as a Surrogate Priest, a scholarly exploration of the priestly and Levitical roots of the rabbinic role, and Converging Destinies: Jews, Christians, and the Mission of God, a historical, theological, and visionary reflection on God’s end-game strategy for Israel and the Church. Currently he is completing a discipling resource for near and new Jewish believers in Yeshua, and devoting himself to research and experimentation with havurah-based spiritual communities. Stuart and his wife, Naomi, have three grown children.

1 Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other (New York: Basic Books, 2017), 280.

2 Jay Y. Kim, Analog Church: Why We Need Real People, Places, and Things in the Digital Age (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP, 2020), 20, 87.

3 Joseph Hellerman, When the Church Was a Family: Recapturing Jesus’ Vision for Authentic Christian Community (Nashville: B & H Academic, 2009), 119.

4 Scripture references are from the Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

5 Read more deeply about the Hebrew bayit in Leo G. Perdue, “The Israelite and Early Jewish Family,” in Leo G. Perdue, et al. Families in Ancient Israel (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1997), 174–75.

6 Hellerman, When the Church, 78–79.

7 “Landsmanshaft,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Landsmanshaft&oldid=1029592500.

8 Israel Goldman, Life-Long Learning among Jews: Adult Education in Judaism from Biblical Times to the Twentieth Century (New York: Ktav, 1975), 173–74.

9 Abraham J. Heschel, God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976), 320.

10 https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/minyan-the-congregational-quorum/

11 Rod Dreher, Live Not by Lies (Penguin, Kindle Edition), 102–03.

12 I got myself in trouble over this issue about twenty years ago when I remarked at a gathering of leaders, “You guys are not prepared to think clearly about the role of gentiles in your congregations because of the financial consequences.” One of the leaders there wheeled around and said, “You’re saying the only reason we have gentiles in our congregations is for their money.” Absolutely false. That is not what I said nor what I meant. But some eighteen years later, one well-known leader among us told me in private conversation that everyone in the room knew I was right. Too bad nobody said anything at the time!

It remains a fair question to ask if the gentiles drawn to our movement are there to help us fulfill God’s purpose for the movement, to be a sign, demonstration, and catalyst of God’s consummating purpose for the Jewish people, or whether they are instead there out of some fascination with Jewish things. That fascination is not a bad thing of course, but it won’t help us get the job done. I have always honored those gentiles who have joined with us as servants of our calling. But we all know of congregations where the agenda is to teach Judaism lite to gentiles, and to fascinate them with a kind of Jewish gnosticism where the “right” interpretation of Scripture is always a Jewish viewpoint unknown to the less enlightened. Such congregations often have few if any Jews, and the kind of teaching I outlined is necessary to keep the lights on and to keep up the appearance of being a successful enterprise. I think we will all agree that this is not missional success, even if it is good business. And that is my point here.

13 British Evolutionary Anthropologist Robin Dunbar and his associates have demonstrated that the maximum number of people with whom any of us can maintain meaningful connection is 140. This is called Dunbar’s Number. “According to Dunbar and many researchers he influenced, this rule of 150 remains true for early hunter-gatherer societies as well as a surprising array of modern groupings: offices, communes, factories, residential campsites, military organisations, 11th Century English villages, even Christmas card lists. Exceed 150, and a network is unlikely to last long or cohere well” (https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20191001-dunbars-number-why-we-can-only-maintain-150-relationships).

Dunbar’s research has also demonstrated factors of crucial import to what will follow in this paper. Our tightest circle of association has just five people, and the maximum number of good friends will be fifteen. Beyond that, he says 150 will be meaningful contacts, 500, acquaintances, and 1500 the number of persons we can recognize. All of this is grounded in cognitive psychology and study of brain capacity. Therefore, don’t expect a rabbi of a congregation over 150 people to have a meaningful connection with all of them. The point is, when we select a bigger-is-better model, we choose superficiality of relationship. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20191001-dunbars-number-why-we-can-only-maintain-150-relationships and also Robin Dunbar, Friends: Understanding the Power of our Most Important Relationships (London: Little, Brown, 2021).

14 Ralph D. Winter, “The Two Structures of God’s Redemptive Mission,” in Ralph D. Winter and Steven C. Hawthorne, eds. Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: A Reader. Third Edition. (Pasadena: William Carey, 1999), 220–30.

15 Andrew Mason’s online presence is no longer active. The group sizes he recommends are compatible with other extant opinions.

16 See, for example, Luke 13:21: “To what shall I compare the kingdom of God? It is like leaven that a woman took and hid in three measures of flour, until it was all leavened.” See also Mark 4:26–32: “And he said, ‘The Kingdom of God is like a man who scatters seed on the ground. Nights he sleeps, days he’s awake; and meanwhile the seeds sprout and grow—how, he doesn’t know. By itself the soil produces a crop—first the stalk, then the head, and finally the full grain in the head. But as soon as the crop is ready, the man comes with his sickle, because it’s harvest-time.’ Yeshua also said, ‘With what can we compare the Kingdom of God? What illustration should we use to describe it? It is like a mustard seed, which, when planted, is the smallest of all the seeds in the field; but after it has been planted, it grows and becomes the largest of all the plants, with such big branches that the birds flying about can build nests in its shade.’”

17 Alan Hirsch, 5Q: Reactivating the Original Intelligence and Capacity of the Body of Christ (100movement.com, 2017).

18 Wolfgang Simson, Houses that Change the World: the Return of the House Churches (Carlisle, Cumbria, U.K., Waynesboro, GA: OM, 2001), 122.

19 References to these foundational home groups are numerous. And the early chapters of Acts position them alongside the larger 5Cs Meetings: “And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they received their food with glad and generous hearts, praising God and having favor with all the people. And the Lord added to their number day by day those who were being saved. . . . And not for a single day, either in the Temple courts or in private homes, did they stop teaching and proclaiming the Good News that Yeshua is the Messiah” (Acts 2:46–47, 5:42). And the foundational text concerning sodalities is in Acts 13:1–3, “In the Antioch congregation were prophets and teachers—Bar-Nabba, Shim’on (known as ‘the Black’), Lucius (from Cyrene), Menachem (who had been brought up with Herod the governor) and Sha’ul. One time when they were worshipping the Lord and fasting, the Ruach HaKodesh said to them, ‘Set aside for me Bar-Nabba and Sha’ul for the work to which I have called them.’ After fasting and praying, they placed their hands on them and sent them off.” In Jewish life, such representatives are termed sh’lichim or m’shulachim, a term perhaps most familiar from the activities of Chabad-Lubavitch.

20 Some of these functions may be evident in some havurot depending upon the gifts, skills, inclinations and desires of their members. Yet, while there is surely some overlap, simply by being a larger gathering, the 5Cs Meeting expresses dynamics and meets needs not otherwise expressed or met.

21 Stuart Dauermann, The Rabbi as a Surrogate Priest (Eugene: Pickwick, 2009), 261–62.