Messianic Jewish Perspectives on Women in Leadership

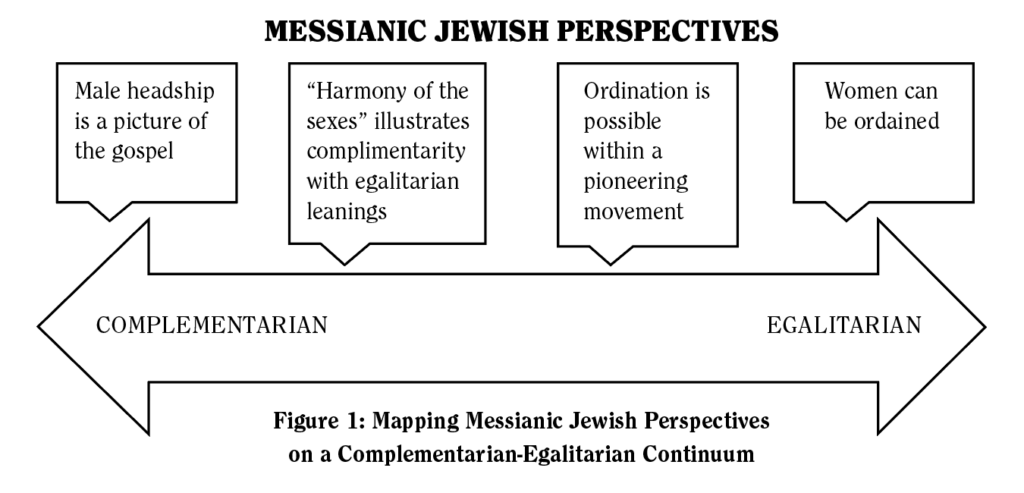

This article will map Messianic Jewish perspectives regarding women in ministry leadership along a complementarian-egalitarian continuum. I will explore four main themes along the continuum: 1) male headship is a picture of the gospel, 2) the “harmony of the sexes”1 illustrates complementarity with egalitarian leanings, 3) ordination is possible within a pioneering movement, and 4) women can be ordained.

Definitions of Terms

Complementarianism is defined as

the position that men and women are complementary to one another, equal in nature yet distinct in relationships and roles. These distinctions are found in (1) the home, with the husband leading and the wife submitting to him; and (2) the church, with men and women serving in all ministries except for elder responsibilities, which are reserved for qualified men. Some complementarians apply this position to distinctions in (3) society, with men leading governments and companies and women serving in positions of lower authority.2

Egalitarianism is defined as

the position that men and women are equal to one another in nature, relationships, and roles. These equalities may be found in (1) the home, with the husband and wife sharing equal authority and submitting to each other; (2) the church, with men and women serving in all its ministries, including elder responsibilities; (3) the society, with men and women leading governments and companies, or (4) some combination of these three.3

Figure 1: Mapping Messianic Jewish Perspectives

on a Complementarian-Egalitarian Continuum

Figure 1 plots four major themes emerging from Messianic Jewish literature regarding women in ministry leadership. These four themes are mapped along a complementarian — egalitarian continuum. The positions of the themes are fluid, are on a sliding scale, and can overlap. For example, “harmony of the sexes”4 is coined by Ruth Fleischer, who received private smikhah (rabbinic ordination); thus, this theme can stretch to the egalitarian side. Also, the “women can be ordained” theme includes authors who believe in the ordination of women as rabbis (Joshua Brumbach5) and the ordination of women as shammashot but not rabbis (Aaron Allsbrook6); thus, this theme can slide from the egalitarian to the complementarian side.

Male Headship

“Male headship is a picture of the gospel” means that the relationship between the husband as head of the household and his wife as his subordinate reflects the relationship between Yeshua as the head of the kahal (congregation) and the kahal as his subordinate bride. “Male headship is a picture of the gospel” sits on the complementarian edge of the continuum. Messianic Jewish proponents of headship as a picture of the gospel view the husband as a picture of Yeshua with the wife as a picture of his body, or congregation. As Yeshua is the head of his body, so the husband is head of his home and of the congregation. Messianic Jewish proponents of male headship as a picture of the gospel include Sam Nadler, Tim Hegg, and Shari Rubinstein.7

Nadler links the home to the congregation as a microcosm of a macrocosm. The head of the house is the man; the head of the congregation is therefore a man. “Therefore, it would seem to be incongruous, to the point of absurdity, to have a woman in a senior leadership position in the congregation when she could not have such a senior leadership position in her own home.”8

Nonetheless, Nadler affirms the equality of men and women and even affirms that the gifts of the Spirit are not gender-specific but are poured out upon all believers. He states, “All of us — both male and female — are to submit our gifts to God for the common good of the body.”9

Sam Nadler believes women can fill any role but the head pastor or rabbi. He bases his view on the lack of biblical precedent for female leaders. Nadler acknowledges the biblical examples of women who operate in support roles in ministry, as prophetesses who can be filled with the Spirit, as a judge like Deborah, as teachers of other women, or as joint teachers of men along with their husbands, like Priscilla and Aquila.10 However, Nadler believes that none of these examples sets a precedent for women to operate at senior leadership levels in a congregation. Instead, he believes that biblical passages such as 1 Corinthians 14:34–35, 1 Timothy 2:8–15, and 1 Timothy 3:1–2 clearly prohibit women from exercising leadership.11 Indeed, the only biblical reference he sees that could possibly indicate a female in congregational leadership occurs in Revelation 3:20, of which he says, “the only insight this would provide would be that it is a sign of disorder.”12

In Nadler’s congregation, women are encouraged to exercise their gifts and are prohibited only from exercising senior congregational leadership or from giving the drash from the bima. They may teach mixed gender adult Shabbat school classes or other congregational classes as long as they are under the authority of the senior male leader. Women may function as staff members, and they may attend board meetings as non-voting participants.13

Tim Hegg, like Nadler, presents a complementarian view that limits women only at the highest levels. According to his view, women can fill any role other than the head pastor or rabbi. If a female leader were to exercise the roles of head pastor or rabbi, Hegg believes that this would cloud the vision of Yeshua as the head of the congregation. Hegg proposes that since male headship is the key to understanding the gospel, therefore, the highest level of leadership must be held by a man.

This authoritative office (called by the title “elder” or “Overseer = bishop”) is reserved for men (males), not because they are better, or more qualified, but because in the economy of the Messianic Assembly, God has set up certain illustrations of the relationship between His Son and His Kehilah. The most important illustration is that of marriage, where the two become one, but where the husband functions as “head” of the wife. If the woman were allowed to take the position of authority in the Messianic Assembly, this illustration would be mixed, and so would the message. For this reason, and this reason alone, women are to function in other teaching capacities, but not in the official office of elder or Overseer.14

For Hegg, male headship as a picture of the gospel is derived from Ephesian 5:24: “as Messiah’s community is submitted to Messiah, so also the wives to their husbands in everything.” Thus, the relationship between the congregation and Messiah is like the relationship between the wife and her husband. In this illustration, the husband strives to be as much like Yeshua as possible, laying down his life for his wife, valuing his wife, and shouldering responsibility as head of the family. “However, as is often the case, it is clear that the husband can never be the head of the wife in exactly the same way as Messiah is the head of the Messianic Assembly. The husband will never be the ‘Savior’ of his wife (Ephesians 5:23) as Messiah is of the church.” 15

Interestingly, Hegg interprets the creation of humankind in Genesis as entailing full equality between male and female, with God’s image portrayed through the complementary aspects of male and female, and with males and females being equally tasked with dominion and rule before the Fall.16 He does not agree that the fact that Adam was created before Eve gives him authority to rule over her, nor does Adam’s naming of her give him authority, since isha is not really a name so much as a recognition of sameness.17 Rather, Hegg roots male leadership in the consequences of the Fall. Although his final conclusions are complementarian, in these points Hegg demonstrates a more egalitarian viewpoint.

Shari Rubinstein presented a paper, which has been revised for publication in this issue of Kesher, at the UMJC’s Summer Family Conference, in which differing views of women in ministry were discussed during a two-hour workshop. As the summer program’s brochure states, “It is strongly emphasized that this workshop is not aiming for any decisions or changes to current UMJC policy [which does not ordain women] but is meant to be educational and informative so that the UMJC members will be better aware of the various interpretations on this topic within the larger religious world and within our UMJC.”18

Shari Rubinstein presents a complementarian view of women in ministry leadership, basing her arguments on difference and distinction for mutual blessing and oneness of spirit.19 She grounds her view in Hashem’s creation of male and female, observing that Hashem’s plans are for male and female to work together.20 She notes that Eve was deceived and sinned first, but Adam was held responsible. Thus, Rubinstein views Hashem’s resulting curses as clarifying male and female gender roles: women are designed to bear children and men are designed to provide for their families. In fulfilling complementary roles, she sees “the fullness of existence” as reconciliation to Hashem.21

After grounding gender roles in creation, Rubinstein addresses the leadership examples of Deborah, Miriam, and the women in the Brit Chadasha. Rubinstein views Deborah’s contribution simply as encouragement that Hashem was with them. She does not see Deborah as a spiritual leader over the army, stating that “nowhere do I read that Deborah would bear the weight if the battle went wrong.”22 Likewise, she notes that Deborah’s husband, Lapidot, is named in the story and concludes from this that “she was submitted to her own husband.”23

Regarding the leadership of Moses, Aaron, and Miriam, Rubinstein acknowledges Miriam as a leader, but not as a “senior leader” in a decision-making role.24 Rubinstein sees the selection of twelve males for the twelve apostles as evidence that women are not spiritual leaders. Although she acknowledges that many women in the Brit Chadasha were disciples of Yeshua, she states that “there is no suggestion in the Gospels of devoted followers necessarily ‘leading’ others beyond the explicit leadership we see of the Twelve.”25

Rubinstein acknowledges the work of Lydia, Nympha, and Priscilla, but does not believe that their “opening their homes for minyans” meant that they were heads of their households or “leaders of those meetings.”26 Likewise, regarding a shammashah (deaconess), such as Phoebe, Rubinstein does not see a precedent for a senior rabbi. First, she sees the office of shammash as “providing fiscal and physical infrastructure for the Gospel to go forth,” rather than as a leadership role. Second, she sees the qualifications for shammashim as being for males specifically, with added qualifications for their wives, not as for male and female shammashim and shammashot.27

Rubinstein concludes her article with an overview of Jewish viewpoints. Considerations that emerge from her overview include 1) Blu Greenberg’s desire to reconcile her love for Judaism with her tendency towards feminism, 2) Kathryn Silberling’s distinctions between women as learners and leaders, 3) Ruth Fleischer’s “changing times must lead to changing roles,” 4) The Jewish Theological Seminary’s majority agreement for ordaining female rabbis, and 5) Sam Nadler’s assertion that women are biblically “restricted” from senior leadership.28

Rubinstein concludes her article by returning to familial gender roles, with extension into congregational community, as Hashem’s plan for mutual blessing. She says, “Some may call it hierarchy, but it seems more like Hashem’s fitting us (back) together to fulfill his purposes.”29

Harmony of the Sexes

“Harmony of the sexes” means that men and women have different but necessary contributions to offer the congregation, similar to an orchestra in which each person playing their instrument contributes to the complete musical piece. Ruth Fleischer seeks the “harmony of the sexes within God’s plan.”30 Using the metaphor of an orchestra, when everyone in the congregation exercises his or her God-given gifts, i.e., metaphorically plays their instruments, the entire congregation is edified, harmony is achieved, and “the Body of Messiah brings honor and praise to our King.”31 Her view acknowledges the differentiation between male and female without limiting the work of God through the ministry roles of either. It also acknowledges the necessity of the full participation of every member. If one instrument is missing, the beauty of the work is lessened. Fleischer’s view is ultimately egalitarian while respecting and appreciating the complementarity between the sexes.

Fleischer discusses the examples of leadership set by Deborah, Huldah, Hadassah, Phoebe, Junia, and Miriam, and, contrary to Nadler’s conclusions, sees these women as legitimate precedents for leadership in the Bible. Regarding these women, she says, “the gifts and calling of God were used as they were given, for purposes which God declared, by their presence in that particular individual. It should be no more difficult to accept this premise for a woman than for a man. Calling has always been God’s provenance, and not the choice of either man or woman.”32

Fleischer believes that the marginalization of women has more to do with history and culture than with a biblical injunction. Throughout history, for most cultures and with few exceptions, women have not been highly valued or well-treated. Women’s emancipation began to change the way women specifically in Judaism and in Christianity have been viewed, but there is still a long way to go. “Far from being an outpost of biblical truth, Judaism has treated its women, especially for the past two thousand years, as the Goyim have treated their women . . . the place of women in organized Christianity was largely one of subservience, ignorance, and powerlessness.”33 Though Conservative and Reform Judaism have opened opportunities for women to serve as ministry leaders and seek ordination, Messianic Judaism has followed the examples of Orthodox Judaism and conservative streams of Christianity. “Some within our movement believe that we should be the head and not the tail in Judaism, and yet, in this area, we are assuredly not leading the way.”34

Fleischer concludes that Messianic Judaism needs the input and participation of called and qualified female leaders:

If we choose to go the way of the Orthodox and of the Roman Catholic Church, we risk losing qualified and called women that are needed in our movement, to other avenues of service and other pursuits outside of the Messianic community. There are few enough leaders to go around as it is without rejecting a handful (there will never be huge numbers of women who want to be Messianic rabbis!) because — and only because — they are women. It is time to rethink history and to note what is happening around us.

Could we be wrong? How will our children and grandchildren judge us on this issue? Will the traditional Jewish community praise us for holding the line on female ordination or will the Reform and Conservative communities count this as yet another area in which we are unwilling to confront the present and cling to “Christian” modes? Will we encourage and motivate women within the movement or will those who are educated and knowledgeable leave us for greener pastures? What does God’s nature really say about his calling upon the lives of individuals, male and female?35

Fleischer’s concluding remarks raise excellent questions regarding the purpose and role of the Messianic Jewish community, how women play into that symphonic picture, and how that picture could be marred with the absence of key female instruments.

Ordination Is Possible

The pioneering nature of Messianic Judaism means that Messianic Judaism breaks the boundaries of traditional interpretations and practices. The theme “ordination is possible within a pioneering movement” is represented by Rachel Wolf, Alec Goldberg, and Vered Hillel.36

Based on Rachel Wolf’s own experience, research, and an informal email survey including forty-seven Messianic Jewish women, Wolf identifies two characteristics that Messianic Jewish women share. First, Messianic Jewish women are pioneers; and second, Messianic Jewish women struggle with identity.37 As pioneers, Messianic Jewish women have contributed much to the movement with little to no recognition. They have built congregations with their husbands, led the way in education, developed music, led prayer, taught Bible studies, started organizations, and served on their boards.38 These pioneers are now Baby Boomers. Some are content with their contributions and do not seek titles or recognition. Others are frustrated. They do all the work of preparing for large conferences and then have to step back while the men take over.39

Defining identity for a Messianic Jewish woman amounts to an “endeavor to navigate a sea of disparate voices coming from traditional Judaism, contemporary Judaism, and conservative Christianity.”40 These voices offer contradictory messages. “Indeed, there is enough seemingly contradictory evidence in Scripture to support either side of the argument, but some feel that traditional role models have been overemphasized.”41 Indeed, Scripture also portrays strong female leaders functioning in roles that appear more traditionally masculine. Therefore, Scripture does not present traditional female roles as “prescriptive or limiting.”42

At the organizational level, women are generally permitted to serve in any role other than that of congregational rabbi, which aligns with a complementarian view. However, Messianic Jewish women range from egalitarian to very conservative. The younger the women, the greater the number of egalitarians. “Younger women tend in greater numbers to advocate for the egalitarian model they see in more liberal forms of Judaism, including ordaining female rabbis.”43

However, out of the forty-seven women that Wolf surveyed, the responses were unanimous that the traditional role of motherhood plays an essential part in the plan of God. “As we rightly lift up women like Deborah and Yael as role models, we should at the same time acknowledge the power of the traditional role of motherhood.”44 As Jew and Gentile are to remain distinct, so men and women also “reveal the image of God in distinct ways.”45

Overall, Wolf presents a view of Messianic Jewish female leadership as one that maintains female distinction, honors traditional roles, and acknowledges the gifts and calling of God that produce women such as Deborah and Yael. Her viewpoint may move the conversation forward within Messianic Judaism and benefit the Body of Messiah by maintaining male and female distinction without precluding ministry leadership roles for women.

Alec Goldberg and David Serner interviewed over 200 leaders of local fellowships in Israel regarding the question of Messianic Jewish women in ministry leadership. The fact that women are highly involved in ministry is a given, but their primary question was “What is the highest position in the congregation available for a woman?”46

According to the figures we obtained after processing all the answers, the Israeli Messianic movement in general is quite open to the idea of women teaching and preaching to men: only 32%, i.e., less than a third of the fellowship, do not accept it. Most unified in support of female teaching ministry are the Spanish- and Amharic-speaking congregations, while the Hebrew-speaking ones are the most conservative, with close to half of them (45%) believing that a woman should not teach a man. The Russian- and English-speaking communities occupy the middle positions between the two aforementioned groups, but of the two the Russians are more conservative.47

Goldberg and Serner also noticed a correlation between more charismatic congregations and less charismatic congregations and their attitudes towards the roles of women in ministry leadership. Those in more charismatic congregations, the Amharic- and Spanish-speaking, are more open to women in leadership positions, whereas the Hebrew-speaking congregations tend to be the least charismatic and the least likely to approve of women in leadership positions.48 Additionally, Goldberg and Serner note a difference between beliefs and practice. Even though a majority percentage of congregational leaders believe women can lead, very few women are actually in leadership.49

Goldberg’s final questions look for the influences behind Israeli perspectives towards women in Messianic Jewish ministry leadership. He concludes that “the influence of Western theology on female leadership and church culture are two likely factors” affecting Israeli perspectives, and “financial support plays by no means the smallest role in this assignment.”50 Goldberg questions the validity of these attitudes for a distinctively Messianic Jewish movement in Israel. He asks, “How authentically Israeli are these solutions?”51

In a joint article, Vered Hillel and Lisa Loden describe pioneering women in Messianic Jewish ministry leadership in Israel, examine the cultural influences that helped shape the current theological landscape, and express the need for a distinctly Messianic Jewish theology that is separate from the Christian mission influence so that women remain in Messianic Jewish congregations, enriching them by contributing their gifts and talents.

Hillel and Loden echo Goldberg’s question of how authentically Messianic Jewish attitudes towards women in Messianic Jewish ministry leadership truly are. Hillel and Loden note the influence of the Southern Baptists in evangelizing Israelis and observe that their theology continues to shape women’s roles. “Leadership roles are the exclusive domain of men according to the patriarchal understanding that women are designed and created to be man’s helpmeet and her domain is that of the home and family.”52 Yet Messianic Jews need distinction — a proper, right, and fitting response to the question of Messianic Jewish women in leadership ministry. Israeli society is largely egalitarian, yet Messianic Judaism practices complementarianism.53 In their conversations with female Messianic Jews in Israel, Hillel and Loden note a distinction in how different generations approach the challenges to ministry. Boomers and Gen Xers typically do not agree with complementarianism, yet proceed to work within the parameters, whereas Millennial and Gen Z women “have a greater tendency to vocalize their objections to the attitude toward and the roles of women emanating from complementarian theology.”54 Several Millennials and Gen Zers are leaving Messianic Judaism, moving either towards independent home congregations or into mainstream Jewish synagogues.55

Women Can Be Ordained

The theme “women can be ordained” includes ordaining women as both shammashot and as rabbis. Ordination of women is represented by Aaron Allsbrook, Paul Saal, and Joshua Brumbach.56

In 2019, the elders of Ohev Yisrael Messianic Congregation made the decision to ordain shammashot (female deacons). Aaron Allsbrook, a rabbi of the congregation, presented a paper to his congregation explaining this decision. His paper was later published as an article in Tikkun America Restore. Ohev’s prior policy of not ordaining women to the office of shammash was based on biblical texts and Messianic tradition. However, additional biblical evidence and the work of the Holy Spirit within their community have convinced the elders at Ohev that ordaining shammashot will honor the work of the Spirit and benefit and encourage their congregation.57

First, Allsbrook defines a shammash, or shammashah, with the Greek diakonos, or deacon, as meaning a “waiter, servant, or steward,” and he sees “a parallel to the chazzan or gabbai who tend[s] to the needs of the synagogue and [makes] sure everything [runs] smoothly.”58 He connects this office to offices within contemporary Jewish synagogues and to Acts 6. He does not see the shammashim as having the ultimate authority or needing to be teachers.59

Second, Allsbrook notes prominent women during Paul’s time. Paul commends these women, even praising Phoebe as a diakonos. Allsbrook considers that this term may be an official title, given that it is the male form of the word applied to Phoebe.60 Allsbrook also notes that some women ran home congregations (Colossians 4:15 and 1 Corinthians 16:19), and he notes the works of Junia and Priscilla.61 These women serve as examples for women today who follow Yeshua as the Messiah.

In his discussion of 1 Timothy 3, Allsbrook contrasts Paul’s qualifications for shammashim versus his qualifications for elders. He concludes that the reference to women in 1 Timothy 3:11 is to shammashot, not to the wives of shammashim.62 Allsbrook views the office of shammashim as that of administrators and states that “certain matters in the congregations are sensitive to females, and such would best be administered by shamashot.”63

Fourth, Allsbrook presents evidence from the early development of Christianity of the existence of shammashot, specifically from Pliny’s execution of two shammashot when they refused to renounce their faith, and from the Church Fathers Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Chrysostom, and Basil of Caesarea.64 Allsbrook sees the disappearance of shammashot as a historical and theological development: “The big change came as the rule developed that one aspiring to be a priest had to first be a deacon. Since women could not be priests, women therefore couldn’t be deacons.”65

Finally, Allsbrook acknowledges that change is difficult, but he calls his congregation to accept shammashot for the following reasons: 1) though Yeshua’s primary disciples were male, he also had many female disciples, 2) although America’s Constitution was first directed primarily to white males, men and women of all colors are included today, 3) Messianic Judaism itself was a radical idea fifty years ago, but “what we take for granted and normal took much prayer, discussion, and presentation of evidence. This is the same situation with the ministry and calling of shamashot.”66 These are excellent points worthy of consideration.

In June 2023, Paul Saal hosted a class through MJTI called “How We Role,” and in this class, he explored the creation of male and female, biblical passages pertaining to women’s roles, and modern implications for our traditional perspectives and practices. He sees in the biblical creation narrative a poetic rather than an empirical diction that expresses a unique relationship between male and female, as a unity of opposites.67 Citing Genesis Rabbah, he quotes: “One being, back to back, God severed them so they could face each other and come together again to be whole.”68

Hence, Saal sees the creation of male and female as equal, as corresponding to one another. Males and females are ontologically equal, and their differences are biological, not sociological. Saal outlines different types and meanings of equality: ontological equality, that all people are created equal in the image of God, is not the same as equalities of opportunity, condition, or outcome.69 Sociologically, inequalities of opportunity, condition, or outcome represent the battleground for equal rights seen today.

The ontological equality of male and female at creation is represented by the ish leaving his family for the isha in Genesis 2:24. A man leaving his family for his wife is not patriarchal. Yet, in a modern ketubah (Jewish wedding contract), the husband purchases his wife, as if she were property.70 What Hashem pronounced good at creation now looks quite different. Something has been broken.

In the beginning, Hashem gave humans charge over the earth and its animals. Genesis Rabbah 8:13 says that if people merit it, they will dominate the animals, but if they do not, then they will be dominated by the animals.71 In the same way, when Adam and Eve broke Hashem’s commandments, they broke his good design. They do not merit it. Hence Adam is dominated by what Hashem used to create him — the adamah or earth, and Eve is dominated by what Hashem used to create her — Adam.

Sin brings brokenness and struggle. Genesis 3:16–19 details the results of sin. Yet, Saal sees that the curse, the present reality, is not the ideal, and he believes that the Body of Messiah should be living towards the eschatological idea, rather than maintaining the order of brokenness.72 If Yeshua has paid the penalty for sin, and he has, then those who are in him are new creations, in the order of God’s good design, not in the order of brokenness. Followers of Messiah have only partially arrived; there must be a continuation on this path of following Messiah and living into his ideal.

In the Bible, narratives are descriptive, not prescriptive. That is, they are haggadic, not halakhic.73 For example, when readers see how many wives Kings David and Solomon had, or that Jacob fathered children with four women, that does not mean that readers should go and do likewise. On the contrary, biblical passages such as Genesis 2:24 and 1 Timothy 3:2 affirm that monogamy is God’s design. Polygamy is included in a description of the reality of how things were, but monogamy is God’s ideal. Polygamy is a symptom of brokenness, whereas monogamy is a fruit of the creative renewal of the Spirit. Polygamy is part of the haggadah, the history of God’s people. Monogamy is part of the halakhahh, God’s command for his people. Yeshua makes this clear in Matthew 19:8 when he says, “Moses permitted you to divorce your wives because your hearts were hard, but it was not this way from the beginning.”

Amazingly, God works in and through imperfect people and their imperfect actions. Saal notes that psychologically, men tend to think in terms of power and keeping it, whereas women tend to use power to accomplish a purpose.74 If complementarianism versus egalitarianism amounts to a power struggle, then egalitarian women are playing a man’s game, but I think that is not the central focus of the current egalitarian movement for women within Messianic Judaism. I think Saal is correct in identifying women’s motivations as for purpose rather than power. Saal describes the “glass ceiling” as a paradigm in which women climb the hierarchal ladder in man’s created structure, and he recommends restructuring the paradigm around a framework of special attributes women can contribute to a leadership team.75 Many Messianic Jewish women who are called by God to ministry leadership wish to use their gifts for the benefit of the congregation; and they often envision doing so alongside men in a shared leadership paradigm.

Change is hard, but Saal cautions against resisting changes to the glass ceiling paradigm. He is concerned that the Messianic movement will age out and die out, not due to age so much as to the inability to change.76 He believes that the Messianic movement is limiting its potential by limiting its perspectives to males only at the leadership level. Adding female perspectives to a leadership team will “better express facets of God’s image.”77 This fuller picture of the image of God will then present a better picture of the Body of Messiah to the greater Jewish community. Saal concludes with three main points worthy of further consideration: first, our current practices are “self-alienating from the greater Jewish community,” as “all but the most conservative haredi ordain women;” second, we are “sending mixed messages to our children,” thus alienating them as well; and third, our present practices are “inconsistent,” creating confusion, organizational issues, and de facto positions.78

Joshua Brumbach has been arguing for the ordination of women as rabbis since at least 2007. He presented a paper entitled “Women Rabbis and Messianic Judaism” in 2012, and “Called to Lead: Women as Spiritual Leaders in Messianic Judaism” in 2023. He gives scriptural and historical precedent for Messianic Judaism to follow all other branches of Judaism in the ordination of female rabbis. From the Tanakh, Brumbach considers the creation of Adam and Eve as equals, and he considers the biblical leadership examples of Miriam, Deborah, Ruth, and Esther.79 Huldah was such a great prophetess that Hilkiah sought out Huldah instead of Jeremiah, and the southern gates in the Second Temple bear her name.80 From the apocryphal writings, Brumbach reminds his readers of Susanna, Judith, and the martyred mother of seven sons. “The Jewish compilers and readers who accepted these books as holy writ apparently had no problem with the central figures of these books being women.”81 Furthermore, two Judean queens reigned: Athaliah in the 9th century BCE and Salome Alexandra during the Hasmonean period.82 From the New Testament, he notes examples of women serving as “disciples, congregational leaders, teachers, prophets, and even apostles.”83 Although women were not part of Yeshua’s inner circle of twelve disciples, many women served within the broader circle of his disciples.84 Today, although there is some overlap between the offices of rabbi and that of Temple priest, the offices are not the same: “Although it is true women did not serve as priests, clergy today are not priests in the biblical/Levitical sense, and therefore do not have the same expectations and requirements.”85 When considering women for rabbinic ordination, it is enough to note women as precedents for leadership over nations, such as queens and judges, and women in direct spiritual positions of leadership, such as apostles, prophets, evangelists, shepherds, and teachers. There are female precedents for all of these.

As Brumbach turns to the writings of Paul, he notes the lack of connection between Paul’s obvious “support and encouragement of women leaders” and contrasting passages which seem to prohibit female leadership.86 In short, he concludes that there is ample textual evidence for Messianic Jewish women serving in prominent positions within the first century Yeshua movement and that “numerous passages that support women in spiritual leadership seem to counterweigh a reading that would oppose women in ministry.”87

Brumbach then proceeds to note the ministry leadership of women in the New Testament Apocrypha, such as Thecla, and that during the Second Temple period, “women served as leaders of synagogues, participated in ritual services, learned and taught Jewish law, were counted in a minyan, and from archaeological evidence, do not seem to have been physically separated from men during prayer.”88 Women participated in the synagogue as synagogue heads, leaders, elders, and prophets.89 The earliest reference to a mechitza appears to be from Abaye in the 4th century CE in the Babylonian Talmud (Kiddushin 81a) and is unrelated to the synagogue, hence “any kind of inference of women’s inferiority and inability to be a spiritual leader based on supposed separation during prayer is not supported by archaeological or textual evidence.”90

Brumbach notes historical considerations for ordaining women rabbis. First, he notes the female Talmudic scholar Beruriah, who was “respected for her knowledge on matters of both halachah and aggadah.”91 In 17th century Kurdistan, Osnat Barazani, a female Torah scholar, led the Mosul Yeshiva “without controversy” and “is still remembered today as a great rabbi and leader within the Kurdish Jewish community.”92 Brumbach also highlights several women Chassidic Rebbes, including the Maiden of Ludmir, Chanah Rachel Verbermacher, Hodel, the daughter of the Baal Shem Tov, her daughter Feige, Rachel, the daughter of Abraham Joshua Heschel, and more.93 These examples demonstrate that there have been historical ebbs and flows to the permissible participation of women in religious leadership. “Although women’s roles became more traditionally subservient to men, with a greater limitation on their ability to fully participate, this was not always the case. There was a time when women were able to participate to a much higher degree within religious life, both in Judaism and in Christianity.”94 When discussing the issue of women’s ordination, many traditionalists within Messianic Judaism believe that the question is borne from the “women’s liberation movement,” or is a “product of more recent social agendas. But this discussion is neither a new phenomenon nor a unique product of the modern world, as many ancient sources also wrestle with similar questions concerning the roles of women.95

Regarding female ordination, Brumbach sees no halakhot specifically prohibiting smikhah. However, there are six objections typically raised against it: that women are ineligible to be leaders, that women are exempt from studying Torah and from fixed prayer, that women are exempt from time-bound mitzvot, that women cannot be counted in a minyan, that women cannot read Torah in public, and that women are not eligible to serve as witnesses in halakhic matters and therefore cannot sign ketubot, gittin, or other legal documents.96

Regarding the first reason, that women are ineligible to be leaders, he affirms that there is nothing in the Torah that prohibits it. He sees this assumption that women cannot be leaders as a Greco-Roman cultural influence. “By the time of the Mishnah (c. 200 CE), a social change due to Greco-Roman influence began to change the openness towards women within Judaism.”97 This attitude from the Greco-Roman culture may have also affected the second and third reasons, those of exempting women from Torah study and from time-bound mitzvot. There is nothing biblically that exempts women from either. Exempting women from Torah study is based on Kiddushin 29b, in which the plural masculine form of the command in Deuteronomy 11:19 to teach Torah to children presumes that only boys are to be taught. However, “when the Torah widely speaks in the masculine plural, it is meant to refer to both men and women.”98 Therefore, Brumbach considers this a weak argument.

I agree with Brumbach that this is a weak argument and would argue that women are indeed required to study Torah. Since women are the primary teachers of young children, it is of necessity that women learn Torah, for they must teach it. The eyshet chayil “speaks with wisdom and has faithful instruction on her tongue (Proverbs 31:26).” Solomon urges his son to “Listen to his father’s instruction and not to forsake his mother’s teaching (Proverbs 1:8).” In contrast, Kiddushin 29b records the following: “whoever is commanded to study Torah is commanded to teach, and whoever is not commanded to study is not commanded to teach. Since a woman is not obligated to learn Torah, she is likewise not obligated to teach it.”99 In this, I believe the baraita has departed from the clear commandments of the Tanakh. Halakhah is meant to be reinterpreted for appropriate application in each generation, and it is time to reconsider the prohibition against women learning and teaching.

Similarly, Brumbach sees the exemption of women from time-bound mitzvot as another weak argument. All of the traditional mitzvot for women, such as “lighting the Shabbat candles, mikveh, challah, sitting in the sukkah, [and] attending a Passover seder,” are all time-bound mitzvot!100 Likewise, he sees that the prohibition against women serving in a minyan is “tenuous,” and repeats that during Second Temple times, it was customary for women to count as part of a minyan and indeed even lead minyanim.101

Regarding women not reading publicly from the Torah, Brumbach points out that the Tosefta permits women and children to be called up for a Torah reading: “The Sages taught that anyone may be called to read from the Torah; even a child and even a woman (Tosefta on Megillah, Chapter 23, Paragraph 11).”102 Even if a woman is menstruating and is thus ritually impure, the Torah cannot be made impure, so this is not a reason to prohibit her.103 The only possible reason to prohibit a woman from reading Torah is because of some vague concerns regarding the “honor” or “dignity of the congregation,” but the meaning of this phrase in Megillah 23a is unclear, and Rabbi Meir of Rothenberg ruled that “where it is impossible to call seven men, the honor of the community must be set aside.”104 Rabbi Joseph Caro, author of the Shulchan Aruch, assumes that “a woman may read from the Torah and recite the appropriate blessings.”105 The “honor of the community” does not concern him. Thus, there is no solid halakhic reason to prohibit women from publicly reading Torah.

The final objection to the ordination of women is significant, for if women are ineligible to serve as witnesses, then they are prohibited from witnessing and signing ketubot and gittin, two important activities of a rabbi. The inability of women to serve as witnesses is attested in rabbinic writings such as the Shulchan Aruch, but this ruling is not biblically based nor is it attributed to the Bible. In fact, this ruling opposes the example of Deborah, a female judge, prophet, and military leader. Mayer Rabinowitz concludes:

The areas from which [women] were excluded are those in which they were considered as not being knowledgeable or reliable due to their lack of interest or experience. . . . The social reality was that woman did not fit the definition of . . . “free adults.” This is no longer the case. Contemporary women have careers, are involved in all kinds of businesses and professions, and have proved to be as competent as men.106

Based on this, Brumbach sees no reason why a woman cannot serve as a witness in halakhic matters and thus why she cannot seek rabbinic ordination.

However, I see the inability of women to serve as witnesses as being a potential problem for female ordination. Traditional Jewish law has not caught up yet with the women’s suffrage movement. In orthodox Jewish tradition, only the husband can give his wife a get, and if he does not, then she is still considered an agunah, or chained woman. She does not have the power to divorce him. Until women have the full rights and freedoms as men in the religious cultures that influence Messianic Judaism, I find it difficult to imagine an ordained female Messianic Jewish rabbi gaining the respect that is due. Though leaders in the Messianic Jewish community may not realize the influence that the attitudes of Orthodox Judaism (and Christianity) have on the decisions that they make, these attitudes continue to chain women. Though male leaders would not overtly support the abuse of women, the fact that agunot still exist in orthodox traditions demonstrates that the men in leadership are not truly viewing women as equally reflecting the image of God. As Brumbach says, “horrific stories abound within the Orthodox world concerning agunot who remain legally chained to their dead-beat and nowhere-to-be-found husbands. Such situations point to the dire need to critically re-read and re-interpret the Bible and halachah.”107 Though Messianic Judaism is not itself within the boundaries of Orthodox Judaism, especially with regards to giving a get, Messianic Judaism is sensitive to and is influenced by Orthodox attitudes, even politically aligning more with the Orthodox than with Conservative or Reform traditions.

Documented discussions of female ordination within Judaism appear from the mid-1800s and are concurrent with the woman’s suffrage movement, again suggesting a link between women’s freedoms and women’s responsibilities to fulfill the call of God in their lives. Brumbach discusses examples of female Jewish rabbis, such as Regina Jones, who was ordained in 1935, served in Berlin, then in the Terezin ghetto, and died in Auschwitz in 1944.108 May her life and death not be forgotten, and may the seeds of her faith produce a harvest! As with the suffrage movement, the movement within Judaism to ordain women has been a lengthy process. “Finally in 1972, Rabbi Sally Priesand became the first ordained woman rabbi in America after graduating from Hebrew Union College — Jewish Institute of Religion. Like Rabbi Regina Jones before her, she was setting a precedent that could no longer be ignored.”109

Reconstructionist and Conservative Judaism now ordain women, and there are over 100 ordained women rabbis within Orthodox Judaism.110 “Many halakhic authorities, both who support and do not support outright smikhah for women, acknowledge that many of these roles are not forbidden to women;”111 and Brumbach notes that support within Orthodoxy for further ordination of women is growing.

In 2011, the Messianic Jewish Rabbinical Council passed a resolution to permit the ordination of female Messianic Jewish rabbis.112 Their resolution is accepted by neither the UMJC nor the MJAA. To date, the MJRC has ordained only one female Messianic Jewish rabbi, Vered Hillel. Ruth Fleischer was ordained privately in 1997; Shirel Dean and Lynn Fineberg also received smikhah privately. Shulamit Goldin and Shari Rubinstein received UMJC’s Madrikh credentials. Brumbach says of these women, they are “pioneers in a movement that has not always been ready for them.”113

Brumbach concludes his 2012 paper by noting the contributions of women rabbis to Judaism and to what it means to be a rabbi. Women have added balance and intimacy and have redefined what it means to be a rabbi, moving the perception from “distant holy man” to a more “creative partnership” that inspires increased participation from congregants.114 Women rabbis have added and continue to add much to Judaism, and Brumbach believes “it is time for Messianic Judaism to join our larger Jewish world in openly ordaining women as Messianic rabbis.”115

Summary

Messianic Jewish perspectives regarding women in ministry leadership can be plotted on a complementarian-egalitarian spectrum.

On the complementarian side, male headship is seen as a picture of the gospel. This view is represented by Sam Nadler, Tim Hegg, and Shari Rubinstein. In this perspective, women cannot function in ministry leadership roles because men are specifically given the role of leadership to represent Messiah. By restricting leadership roles to men, men and women will present a picture of Messiah and his kahal.

“Harmony of the sexes” illustrates complementarity with egalitarian leanings. This view is represented by Ruth Fleischer, who coined the phrase “harmony of the sexes.” In her perspective, women’s voices represent key instruments in the symphony of life, and she suggests that practices that lean too far towards the complementarian side of the spectrum silence women’s voices, negatively affecting the harmony of the whole. Her view acknowledges the beauty and necessity of complementarity without the necessity of subordination.

Moving along the spectrum towards the egalitarian side, Rachel Wolf, Alec Goldberg, Vered Hillel, and Lisa Loden view ordination as a possibility within a pioneering movement. The authors with this perspective honor the traditional roles of women while also recognizing women’s ministry leadership contributions to the development of Messianic Judaism. This viewpoint is concerned with the need to develop a theology of women in ministry leadership that is distinctly Messianic Jewish.

Finally, the theme “women can be ordained” is represented by Aaron Allsbrook, Paul Saal, and Joshua Brumbach. Allsbrook argues for the ordination of women as shammashot, while Saal and Brumbach see no reason — biblical, cultural, or halakhic — why women could not be ordained as rabbis. Thus, Messianic Jewish perspectives concerning women in ministry leadership vary widely and represent the diversity within our movement.

Elisa Norman, MTS Brite Divinity School, is completing the requirements for a DMin in Messianic Jewish Studies from The King’s University in Southlake, TX (expected graduation May 2024). She and her family serve at Eitz Chaim in Plano, TX. Highlights of her service include teaching, developing curricula, and creating weekly children’s videos, shown to the congregation during services and posted on youtube: Eitz Chaim Children. This article was adapted from the literature review chapter of her doctoral project, a grounded theory study of women in Messianic Jewish ministry leadership. A future Kesher article will discuss the findings of her project in light of the findings of the UMJC’s 2022 Dorot study.

1 Ruth Fleischer, “Women Can Be in Leadership,” Voices of Messianic Judaism, ed. Dan Cohn-Sherbok (Baltimore: Lederer, 2001), 151.

2 Gregg R. Allison, The Baker Compact Dictionary of Theological Terms (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2016), Kindle edition, 46–47.

3 Allison, 79.

4 Fleischer, 151.

5 Joshua Brumbach, “Called to Lead: Women as Spiritual Leaders in Messianic Judaism,” Kesher, Issue 44, (Winter/Spring 2024): 3–4.

6 Aaron Allsbrook, “On Ordaining Shamashot: The Calling of Women for Ministry in the Messianic Community,” Tikkun America Restore 10 (June 2022): 50.

7 Sam Nadler, “Male Leadership and the Role of Women,” Voices of Messianic Judaism; Tim Hegg, “The Role of Women in the Messianic Assembly,” Torah Resource (Tacoma, WA: Torah Resource, 1988); Shari Rubinstein, “Should Women Be Credentialed as Rabbis?” Kesher, Issue 44, (Winter/Spring 2024): 25–38. Tim Hegg sits outside the communal boundaries of Messianic Judaism due to his strong One Law stance, but his teachings remain influential within Messianic Jewish congregants and Hebrew Roots followers.

8 Nadler, 164.

9 Nadler, 165.

10 Nadler, 159–62.

11 Nadler, 163.

12 Nadler, 163.

13 Nadler, 166–67.

14 Hegg, 43.

15 Hegg, 21.

16 Hegg, 10.

17 Hegg, 12–14.

18 “Summer Family Conference Program Guide,” Union (Columbus, OH: UMJC, 2023), 16.

19 Rubinstein, 25.

20 Rubinstein, 25.

21 Rubinstein, 26.

22 Rubinstein, 28.

23 Rubinstein, 28.

24 Rubinstein, 28.

25 Rubinstein, 29.

26 Rubinstein, 30.

27 Rubinstein, 31.

28 Rubinstein, 31–34.

29 Rubinstein, 36.

30 Fleischer, 151.

31 Fleischer, 151–52.

32 Fleischer, 153.

33 Fleischer, 154–55.

34 Fleischer, 155.

35 Fleischer, 156.

36 Rachel Wolf, “Messianic Judaism and Women,” Introduction to Messianic Judaism, eds. David Rudolph and Joel Willitts (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2013); Alec Goldberg, “The Israeli Take on the Female Question,” Mishkan 84 (Fall 2021); Hillel and Loden, “The Place of Women in the Messianic Jewish Community,” Mishkan 84 (Fall 2021).

37 Wolf, 98.

38 Wolf, 99–100.

39 Wolf, 103.

40 Wolf, 98.

41 Wolf, 103.

42 Wolf, 104.

43 Wolf, 103.

44 Wolf, 105.

45 Wolf, 104.

46 Goldberg, 108.

47 Goldberg, 108.

48 Goldberg, 109.

49 Goldberg, 109.

50 Goldberg, 110.

51 Goldberg, 110.

52 Hillel and Loden, 113.

53 Hillel and Loden, 115.

54 Hillel and Loden, 117.

55 Hillel and Loden, 117.

56 Aaron Allsbrook, “On Ordaining Shamashot,” Tikkun America Restore 10 (June 2022): 26–29, 50–51; Paul Saal, “How We Role,” Messianic Jewish Theological Institute (Online class: MJTI, June 2023); Joshua Brumbach, Called to Lead; Joshua Brumbach, Women Rabbis and Messianic Judaism (paper presented to the Messianic Jewish Rabbinical Council, February 2012).

57 Allsbrook, 50.

58 Allsbrook, 26–27.

59 Allsbrook, 27.

60 Allsbrook, 28.

61 Allsbrook, 28.

62 Allsbrook, 28.

63 Allsbrook, 29.

64 Allsbrook, 29.

65 Allsbrook, 29.

66 Allsbrook, 50.

67 Saal, “How We Role,” Class lecture, 13 June 2023.

68 Bereshit Rabbah 8:1, sefaria.org.

69 Saal, “How We Role.” Class lecture, 13 June 2023.

70 Saal, “How We Role,” Class lecture, 13 June 2023.

71 Bereshit Rabbah 8:13, sefaria.org.

72 Saal, “How We Role,” Class lecture, 13, June 2023.

73 Saal, “How We Role,” Class discussion, 27 June 2023.

74 Saal, “How We Role,” Class discussion, 13 June 2023.

75 Saal, “How We Role,” Class lecture, 27 June 2023.

76 Saal, “How We Role,” Class discussion, 27 June 2023.

77 Saal, “How We Role,” Class discussion, 27 June 2023.

78 Saal, “How We Role,” Class lecture, 27 June 2023.

79 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 2.

80 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 5.

81 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 3.

82 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 6.

83 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 3.

84 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 4.

85 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 6.

86 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 5.

87 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 8.

88 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 9.

89 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 12.

90 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 13.

91 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 13.

92 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 13.

93 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 14.

94 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 13.

95 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 3.

96 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 12.

97 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 13.

98 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 14.

99 B. Kidd. 29b, trans. Davidson.

100 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 14.

101 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 17.

102 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 17.

103 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 18.

104 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 18.

105 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 18.

106 Mayer Rabinowitz, “An Advocate’s Halakhic Responses on the Ordination of Women,” The Ordination of Women as Rabbis, ed. Simon Greenberg (New York: JTS Press, 1988), 118–9, quoted in Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 19.

107 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 23.

108 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 22.

109 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 24.

110 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 19.

111 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 20.

112 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 27.

113 Brumbach, Called to Lead, 21.

114 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 29.

115 Brumbach, Women Rabbis, 30.